Safety Suggestions to Keep Everyone Alive

[October 2013] Perhaps the most pressure-packed part of a broadcast engineer’s life is dealing with off-air situations. Besides the pressure of figuring out what is wrong with gear that runs high voltages and/or currents, there often also is a barrage of phone calls and/or visitors asking “What’s wrong? When will we be back up?”

As Richard Rudman points out, a focused engineer is a safe engineer.

Promoting on-site safety costs relatively little. But it can prevent expensive and damaging accidents, both to equipment and – more importantly – to personnel. That means you!

Whether a station is off the air or the engineer just has arrived for routine maintenance, it is important to know about and identify dangerous voltages, currents, or other physical dangers.

The biggest mistake that can be made on site is to allow anything or anyone to pressure you or distract you from your task.

By taking time to do the job carefully, and not allowing outside issues or people to rush or to pressure you, you will be much more likely to live to engineer another day. Just think for a moment: when was the last time you saw a good tower rigger allow himself to be rushed?

The point should be obvious.

Plan to be Safe

Here are some suggestions that you can put into practice before doing any work at your facility, even during those pressure-packed “we’re off the air!” emergencies.

By having a plan in place – especially if your General Manager blesses it – you will go a long way toward reducing the possibility of accident or death on the job.

Whenever you arrive on site use the following checklist along with whatever additions are reasonable at your location, It will help keep yourself alive and safe.

First Things First

- Do not work alone. Ask for a person to stand by to watch or help while you tackle potentially dangerous circuits (or other potentially dangerous conditions). This includes, but is not limited to, climbing tall extension ladders.

- If you must work alone at a remote site or hilltop, call someone off-site to tell them you will call back when you are clear, and to send help if you are not heard from by a set time.

- Disable the remote control system. You do not want a shift change to allow someone new coming in and “trying” to get the transmitter back up while you are inside of it.

- Avoid the telephone. One of the most important things a second person on site can do, aside from keeping an eye on your safety, is to field the telephone calls so you are not spending time explaining things nor are you distracted by the constant ringing. Some techs will even turn the phone off until repairs are finished.

Know the Status of All Gear

- Always test whatever gear you are working on with a meter or other device you use to see if circuits are alive or dead. Test the test gear first on a known live circuit.

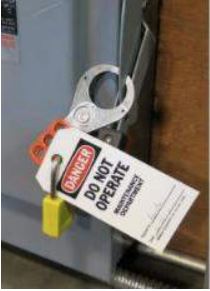

- Buy a “Lock-Out / Tag-Out” kit from Grainger or some other supplier of safety equipment.

- Use the “Lock-Out / Tag-Out” kit! whenever you have to deactivate breakers in order to work on equipment.

This is especially important if the facility is shared – or there are just a lot of different people who may have access while you are fixing whatever it is you turned off the breaker to work on.

This is not just for electrical safety. Machinery that starts to rotate when you least want it to do ao because some dolt turned on a breaker could lead to a trip to the site medical kit for you, if you are able to crawl to it.

- Carefully check the labeling of all breakers in your facility. How often have you found a breaker labeled for some circuit actually turned something else off? (This suggests a good project for a non-emergency maintenance visit.)

Do Not Trust – Verify!

- Always assume any transmitter you work on for the first time has defeated interlocks and/or other conditions that could send you to the morgue. (When you find out your assumption was correct, set things right!)

- Always check the connections and cable integrity of the built-in shorting sticks, interlocks, and bleeder resistors, especially on older transmitters and RF cabinets. Over time, many of these can become ineffective.

- After checking those shorting sticks, use them each and every time before you touch the gear! Use them even if you do not think there is high voltage in the area in which you are working. It is not a bad idea to lay the sticks across the high voltage connections while you are working. Some people even use battery jumper cables to short across tower bases, for example.

More Safe Practices

- Keep one hand in a pocket until you are sure the gear is completely safe. This prevents a circuit from being completed through your body. Remember: it takes only 50 milliamps or less to stop your heart.

- Remove metal jewelry from your arms and fingers when working on electronics. Never mind 110 Volts of AC; just think of what a metal ring could do to your ability to shake hands after a too-close encounter with a low voltage DC circuit that has appreciable amperage.

- Remember that wet floors near electrical panels can be hazardous to your health.

- Whenever possible, take CPR classes and encourage co-workers to do the same.

And Above All

- Avoid working on potentially hot circuits while you are stressed, angry, rushed, tired – or hungry. If you are already off the air, listeners are elsewhere. Take the time to stop, rest, think. The result will be that you are more effective and quicker in fixing the problem.

Be careful, be safe, stay alive! Remember, a dead engineer cannot fix anything.

– – –

A broadcast engineer with extensive experience from small to major markets, Richard Rudman is a regular contributor to the BDR and is the owner of Remote Possibilities in Santa Paula, CA. Contact him at rar01@mac.com