Nathan Subblefield – Did He Invent Radio?

[May 2021] It was 113 years ago when Nathan Stubblefield was awarded a Patent for “wireless telephone.” Yet, despite a number of extremely vocal proponents, Stubblefield was never given the acclaim he desired. Still, his efforts were worth remembering.

As historians look at inventions, it is sometimes difficult to know exactly what was invented and what just “happened” serendipitously. Even the inventors do not always know what they have until others see and put something to use.

Nathan Subblefield might well be in that category. Self-educated in sciences, in the late 1800s and early 1900’s Nathan Stubblefield became known for a series of inventions.

As early as 1892, Stubblefield had made a communications device that he used to transmit speech to his friend Rainey Wells: “Hello Rainey.” But he was best known for the January 1, 1902 demonstration in his hometown of Murray KY, where “hundreds” of people were said to witness his clear transmitting to seven locations his greetings, music, and conversations.

Stubblefield stated he had “solved the problem of telephoning without wires through the earth, as Signor Marconi has of sending signals through space,” and would be capable of sending “general news of every description.”

A WHIFF OF SUCCESS

This got the attention of a group of investors who had formed a corporation to promote and commercialize the wireless telephone. However, Stubblefield soon found himself at odds with the way things were going, and he returned to Murray, where he continued to develop his invention, reaching distances of more than a third of a mile over land and water – and a report in the Scientific American.

More work led to transmission distances of some 1600 meters (one mile) and, later, distances of “less than ten miles.” This led to his being granted U.S. Patent 887,357 on May 10, 1908.

Nathan Subblefield, circa 1908

A 1908 article in the Hopkinsville South Kentuckian quoted Stubblefield saying “You may say that I claim with certain arrangements of apparatus known to myself that I can transmit wireless telephone messages any distance.”

TELEPHONY

As used in those days after Alexander Graham Bell had invented the telephone, telephony meant the sending of audio over distances. Stubblefield wanted to keep the clear transmission of speech, but eliminate the wired aspect.

Of course, as a wireless communication, it could be heard by anyone with a receiver. As part of the Patent application, Stubblefield asserted his invention would be useable for reception on passing trains, boats, and wagons and eventually he would find a way to provide privacy, by “tuning the transmitting and receiving instruments so that each will answer only to its mate.”

Even after setting a goal of transmitting across the Atlantic Ocean, Stubblefield’s work was nevertheless overshadowed by vacuum tube transmitters, which rapidly increased the range of reception, and essentially came to a halt.

WAS IT RADIO?

Aside from the 1908 Patent application, many of the technical details of Stubblefield’s experiments were never written down. All we have today are descriptions from witnesses and friends.

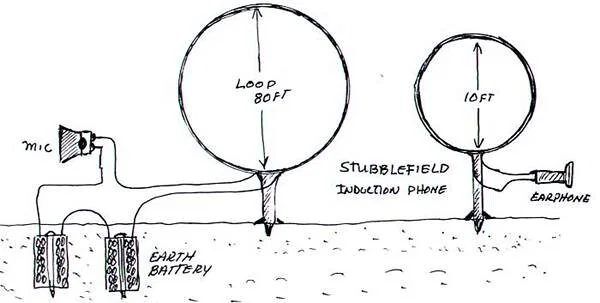

Going by descriptions from others, most historians feel Stubblefield’s early work involved induction, which may have partially been drawn from Amos Dolbear’s work on another wireless telephone system. Later references discuss earth currents as his mechanism.

Because later references refer to earth connections, it appears that Stubblefield subsequently switched to using ground currents instead of induction. Without getting into a deep scientific explanation, perhaps it will suffice to note that Stubblefield used natural conduction – a magnetic field produced by electrical current. Radio, as we know it, is produced by electromagnetic field, similar to a light wave. (By the way, Alexander Bell himself used a light beam to transmit voice in 1892.)

The Stubblefield Induction Phone

Similar, yes. The same, no. And with Stubblefield’s secrecy – and later seclusion – we are left with the general consensus that his invention was an important road on the way to developing radio as we know it.

UNHAPPY ENDING

When radio broadcasting came into the picture, Stubblefield lost support and apparently developed into a paranoid person.

He cut himself off from family and friends. His wife left him, his children sold the family farm, and Stubblefield became a recluse who died of starvation or heart disease in March 1928.

He is honored by, among other plaques, an historical marker – #87 – on the Murray State University campus.

– – –

Would you like to know when more articles like this are posted? It takes just 30 seconds to sign up – right here – for the one-time-a-week BDR Newsletter

– – –