A History of Audio Processing Part 1

by Jim Somich and Barry Mishkind

[July 2018] Before his untimely death in 2007, Jim Somich and I had a number of conversations by phone and email as we discussed the history of broadcast audio processing and laid the basis for a series of articles. With the passage of time, I and some friends decided to update the discussion.

For those that do not know either of us, we both had been involved in the production of some of the processors that gave radio a loud, clean voice in the 70s and 80s, and we had watched the changes over the years, from simple levelers to the microprocessor-driven digital processors of today. While these articles cover a lot of interesting history, it also takes a peek at the current state of the art – and where we may be headed. Jim Somich took the lead on this guided tour. I get to help finish it off as a tribute to a great radio engineer.

The point of audio processing is to transform the program audio so that it will modulate the transmitter in the best possible way: loud and clean.

Way back when in the early days of broadcasting, audio processing was a manual affair. Operators sat at a console with the sole job of keeping the audio at a constant level – and even more importantly – preventing the program audio from jumping high enough to hit -100%, pinch the carrier off and knock the station off the air.

As well, if the modulation current went too high, it could damage the transmitter tubes, knocking the station off the air.)

As well, if the modulation current went too high, it could damage the transmitter tubes, knocking the station off the air.)

With well-trained board operators, stations might achieve an average modulation level (RMS) in the 25% range. Yet with an unobservant or inexperienced operator, the peaks could go all over the place.

Corralling Peaks

When audio processing gear first appeared in the 1930s, its primary purpose was to automate most of the transmitter protection, replacing the operator with an electronic guardian.

Peaks now were kept to limited levels, both positive and negative. For obvious reasons, the new gear was called “limiters.” Many industry engineers worked to design better limiting circuits.

One of the first commercially available limiters was the RCA Model 96-A

Over time, improvements in limiters – and later companion audio compressors – resulted in raising average levels (RMS) transmitted, first to the 35% range in the 1930s and 1940s era, perhaps 60 – 70% in the 50’s, and as high as 85% in the 60s. As a result, the life-span of the transmitter modulation transformers designed in the 30’s was often rather short.

In the 1980s, at the peak of the Modulation Wars solid-state audio processors were driven so hard that at some stations dynamic range was almost eliminated. In some cases, the TSLs (Time Spent Listening) started to drop dramatically.

My prediction is that the processing business will change radically over the next few years – and in a decade you will not even recognize it! (Editor’s note: indeed there have been some very interesting changes, indeed, but we will discuss that in detail a bit later on in this series.)

The Purpose of this History

The importance of what some might consider the arcane field of broadcast audio processing is evident by the extensive work done in the field since the earliest days.

From PROGARS through Uni-Levels and StaLevels, into the Audimax years, the strong Optimod vs. Omnia competition, and now with the wide variety of digital units available, audio processing was evolving into an wht can be called an artform to be mastered by a select adventure-some few.

But this is not merely an historical discussion. To be prepared for the acutely competitive future, we are better off when we know a little about the past and a lot about the present.

Our goal with this discussion is to remember and review the past, take a lingering look at the present, and provide a glimpse into the future of broadcast audio processing – written by someone who has “been there, done that.”

Why This Topic is Important

Today, the audio processor is, in many ways, the heart of a modern broadcast station. It takes whatever audio input it gets and turns it into a consistent “sound signature.” In fact, in many cases, it is possible to visit a market and immediately identify who owns or set up the audio processing at each of the stations just by listening.

One of the reasons this is possible is that virtually every current audio processor is now controlled by one or more microprocessors. From wide-band leveling to multi-channel, stereogenerating, look-ahead limiting, and diversity delay capable, the user has a tremendous set of tools at hand to craft advances in sound processsing.

The Golden Ears

One thing is for sure: even those with so-called “Golden Ears” do not know all there is regarding the ultimate audio processing.

Indeed, there will be new players on the scene along with many of today’s superstars. I, for one, cannot wait to hear what they accomplish. While some actively attempt to re-create the sound of the tube processors, the leading designers already are looking ahead to new horizons of audio control.

The names are legendary and relatively few (in no particular order): Emil Torick, Mike Dorrough, Bob Orban, Ron Jones, Frank Foti, Glen Clark, Greg Ogonowski, Eric Small, Steve Hnat, Donn Werbach, and Jim Wood. Each had a vision of the way radio should sound and made it happen. What a heritage: Audimaxes, DAPs, Optimods, Omnias, Aphexes, and more!

Through the years, more and more sophisticated and creative ways to process audio and snag listeners were pioneered. Just like the record producers, each one had their own ideas on how to build the best sounding radio stations.

Some opted for a wide, open dynamic range while others looked to enhance the “wall of sound” format popular among the record producers. Inevitably, a few simply wanted to be loud and turned their processsor up to “11.”

Yes, the controversial world of modern audio processing definitely continues.

Adapt, Improve, Overcome

Over the years, various exceptional station engineers found innovative ways to overcome the technological limitations of the time by modifying boxes to perform tricks never anticipated by their developers.

Another group went further and designed their own processors from the ground up. Many of these custom boxes were literally built in garages and sold to the industry.

As you will see, successful audio processing has not always been the province of large companyies or groups of engineers. In most cases, it was a lone engineer with a vision who struck out on his own to capture his aural imagination in his own “magic box.”

It may not be as easy to hotrod a DSP processor today the way one used to be able to change some component values in an Optimod or a DAP. But I do know one thing for sure: as I said before, there will be a new generation of processing gurus and they will have new ideas. They will do things with their boxes that we have not even dreamed about as yet.

Who will be these gurus of tomorrow? And what will they have to work with? They are already out there, working in the trenches. Guys like Scott Incz, Corny Gould, and John Burnill have dreams that just might come true.

The Processing Time Machine: Yesterday

As mentioned earlier: in the beginning there was no audio processing.

AM radio stations used the technique of “manual gain riding” to avoid over-modulation – a real live person sat with his hand on the knob, trying to anticipate what was to come next.

With good operators, the practice was reasonably successful, but hardly efficient. The result was low modulation levels– perhaps 25% on average.

Failure to properly anticipate just one spike in the audio level could result in the transmitter overloading and dropping off the air – or worse.

Even the huge 500 kilowatt transmitter at WLW operated in the mid-1930s with manual control to prevent over-modulation. If you are able to see some of the transmitter logs from that time, you will see they have many descriptions of outages caused by modulation peaks.

Most were brief interruptions – a few seconds – but some notes indicated blown-up capacitors, tube failures, and other problems that took longer to repair.

From Manual to Automatic

Gain riding really was an art itself, and it was practiced diligently by the studio engineers of the 1930s, 1940s, and right into the 1950s.

When I started at WGAR, in 1959, almost all gain control still was done manually. Fortunately, by that time, we had a GE BA-5 peak limiter at the transmitter for over-modulation protection. It was not quite a brick wall, but it really helped.

When I started at WGAR, in 1959, almost all gain control still was done manually. Fortunately, by that time, we had a GE BA-5 peak limiter at the transmitter for over-modulation protection. It was not quite a brick wall, but it really helped.

Since one of the primary duties of a studio “engineer” was to ride the gain, there was not a compressor in the entire studio plant.

Talk about pressure. The Chief Engineer at WGAR had installed a chart recorder in Master Control to make a permanent record of the program level going to the transmitter every minute of every day. Each morning, one of his first stops was at the chart to check up on the gain riding of the engineering staff during the past 24 hours. Each engineer was held completely accountable for his shift.

However, with the advent of post-Television radio broadcasting, with its combo operation, fast-paced shows, short jingles, and other multiple elements, the need for an automatic form of gain riding became inescapable.

In our next installment, we will discuss how limiters and compressors because essential to broadcasting, and how the designs progressed.

– – –

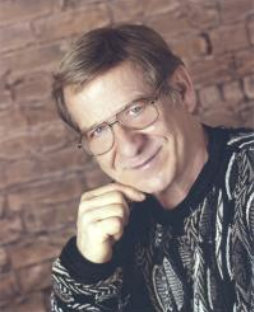

Jim Somich passed away early in 2007 at the age of 65. Among his many achievements, he worked at such major stations as KFI, KMET, WMMS, WHK, WHTZ, WJW.

He was actively interested in audio processing, pushing the envelope at his company, MicroCom Systems. He also served as Director of Radio Engineering at Malrite Communications.

Jim was also very generous with his time, making room to help a number of broadcast engineers to get started.

– – –

The History of Audio Processing Continues with PART 2: Building Better Automatic Control

– – –

Are articles like this helpful to you? If so, you are invited to sign up for the one-time-a-week.BDR Newsletter.

It takes only 30 seconds by clicking here.

– – –