The “Nemo”

[May 2013] We often use terms and phrases, and wonder just where they came from. In this article, Donna Halper explains a term that essentially has come and gone, except as a footnote in history – a colorful one at that.

As with much of the world, broadcasters have always spoken a sort of different language. For one example, in radio’s early years Jack Dodge of WNAC was known as one of Boston’s best “pick up men.”

That was not to mean he was popular with the ladies, although he well might have been because Dodge was young, handsome, and single. Actually, it meant he was an engineer experienced at handling broadcasts at places away from the main studios called “pick-ups.”

In between those years when they were called pick-ups and the modern terminology of remote broadcast, those events from outside the station’s studios had another special name: from the mid-1920s into the 1950s, they were called a “nemo.”

How that name came about is the subject of much debate among media historians.

Word Origin

One thing is certain: the name Nemo was already very well-known in popular culture during the 19-teens and early 20s. Children in school studying The Odyssey would have learned that Odysseus used Nemo (the Latin for no-one or no man) when asked his name by the monster Cyclops.

Then there was Captain Nemo, the enigmatic protagonist in Jules Verne’s famous adventure story 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

And in 1905, pioneering cartoonist Winsor McCay began drawing a critically-acclaimed comic strip called Little Nemo, about a young boy who had amazing adventures in a mythical place called Slumberland. Little Nemo was syndicated in major newspapers for over a decade and it became an animated film as well as a children’s game.

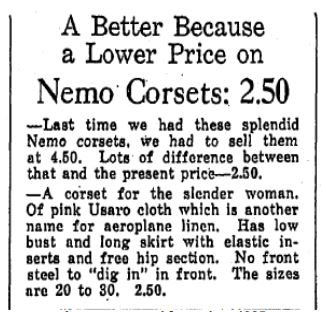

Furthermore, if you were a woman living in the around the turn of the 20th century, you were very familiar with Nemo as the brand name for a popular corset that helped women to achieve the impossibly slender waist expected in the era from the 1890s through the 1930s (it was first advertised in women’s magazines in 1895).

A newspaper ad from circa 1925

Adapted to Radio

So, how did the word nemo enter the world of broadcasting?

Contrary to some stories, it does not seem to have been somebody’s last name, nor does it seem to be the initials for an acronym meaning “not emanating [from] main office,” an explanation that was suggested years after the term was in common use.

Exactly when nemo was first uttered by a broadcaster is difficult to say, but we do know that in 1925 the local New York papers noted the appearance of the “Nemo Male Quartet” (possibly based at the Nemo Theater at 110th and Broadway).

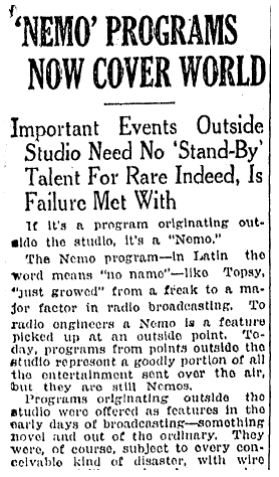

Additional media mention of the term came in mid-July 1927. At that time, several articles from the RCA/NBC publicity department began appearing in major newspapers like the Washington Post, Dallas Morning News and the New York Times.

Published Usage

In those stories, nemo was described as a “coined word, of no original technical significance.”

The articles claimed “nemo” was an accidental exclamation by George Edwin Stewart, an NBC engineering supervisor at WEAF in New York.

According to the accounts, he was hurriedly giving instructions in preparation for a remote broadcast and stumbled over some of his words. What he said sounded like nemo, which evidently struck his colleague as amusing.

It caught on quickly as thereafter, whenever it was time to do a remote, you could hear the term nemo being repeated around the station.

In early December 1928, further explanation was offered, in an article in the Riverside (CA) Daily Press about the origins of new words. In this version, the word “nemo” was said to be “pure Latin for nobody.”

The article said that “radio broadcasting technicians” use this word, or speak about a “nemo station” when describing “the stadium, hall or distant station from which a program is being transmitted to the broadcasting station over a telephone wire.”

By 1929, the word was sufficiently well-known in radio circles that Dr. Frank H. Vizetelly, editor of the Funk & Wagnall’s Standard Dictionary, told a reporter he had heard of a “nemo job,” referring to setting up a remote control broadcast.

No One to See Here

These explanations were expanded in February of 1932 when a New York Times article asserted the NBC engineer had not stumbled at all.

This article said the engineer, impatient when no one on staff could agree upon a word to refer to the button on the control panel that would be bringing in the remote broadcasts, told his colleagues they might as well choose the word nemo because it meant “no name” – and get back to work.

For this explanation to be true, we would have to assume the engineer in question knew Latin or had studied Greek mythology. But this usage of nemo actually makes sense – the person standing in the studio could not see the performers at the remote location.

So, as the music or voice was coming in through the control panel, in the main studio it would have appeared as if no one was broadcasting.

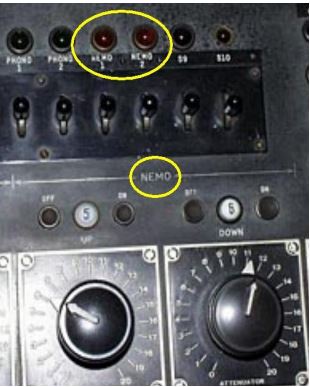

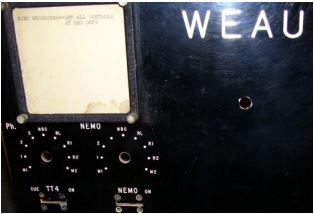

One way or another, the term stuck. Eventually, the word was taped, then engraved, on console inputs and patch bays. In the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s; many consoles were factory labeled with NEMO on at least one input selector switch. The old RCA BC-7 consoles came with stick-on labels; NEMO was one of them.

NEMO inputs could be assigned to pots 5 or 6

No One Knows Why

Nevertheless, although these RCA/NBC-derived stories are certainly possible – and nemo was widely used as radio slang by the early 1930s – radio editors in a number of cities continued to say they had no idea where the term originated.

For example, in early 1932, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times went to the studios of KHJ to do a behind-the-scenes look at how broadcasting took place.

In the article, the reporter described the duties of the announcer, and noted what each button on the control panel did.

His entry for “Button number 6” was that this button was called nemo at KHJ, “for some unknown reason. It takes care of all the network programs and the remote broadcasts.”

Part of a switch panel from WEAU

An Integral Part of Radio

Whatever you call them, remote broadcasts have been around in one form or another since radio’s inception.

Some of the earliest were literally made via wires strung from a hotel ballroom and run back to the radio station’s transmitter. In those days, when audiotape did not exist and all remote broadcasts were done “live,” setting up a remote was not easy.

While some sites did have microphones and wiring ready for use, most locations did not. In any event, except for a few well-stocked sites, doing a remote broadcast meant the pick- up men had to be at the location at least an hour beforehand to make sure everything was working properly.

They would put their equipment into a truck and drive it to the remote site, where it was installed for the day.

Those “pick-up men” then would check all of the microphones and telephone lines that would be used. At New York City’s Capitol Theater, where the popular show “Roxy and His Gang” originated, there were sometimes as many as sixteen mikes in use during the live broadcasts.

As part of the setup, everything had to be coordinated with the announcer back at the studio so that he or she would know when to come in with a station ID or a commercial.

Yet, despite all this preparation, sometimes the wrong button was pushed or a cue was missed. In fact, the article shown above went on to point out how fragile the links were – quite often the lines failed, necessitating a studio orchestra and/or an announcer to cover while “adjustments” were made.

Remote broadcasts were not always easy

Everyone Loved No One

But even when the broadcast was not perfect, it was all worth it.

The nemo became one of radios’ most popular features. The public was fascinated to be able to watch how broadcasting was done, and to meet (or at least see) the performers.

To this day, although we call it a remote rather than a nemo, the pick-up men no longer spend hours setting up – and it might take one person just a few minutes to set up.

Still, people will gather to watch their favorite announcers as they broadcast live, just as they did back in the early 1920s.

– – –

Media Historian Donna L. Halper writes on a variety of radio historical topics when she is not consulting radio stations, writing books, or teaching at Lesley University, Cambridge MA.

You can contact her at: dlh@donnahalper.com