Centenary Radio: The KYW Story – Part 2 The Station That Really Moved Around

[January 2022] Over the years, many stations have changed their frequency, sometimes even their City of License. Especially in the 1920’s and 1941 the FCC – or FRC before it – mandated the changes. But few were as convoluted and covered the length of time as did KYW’s odyssey. Here is Part 2 of Donna Halper’s look at a pioneer station that recently turned 100 – and its travels.

In its early years in Chicago, KYW had moved from 833 kHz to 870 kHz to 560 kHz to 570 kHz to 1020 kHz. One might have thought that was enough. But KYW had some more moves in store.

However, even with power increasing from 1,000 Watts to 2,500 Watts to 5,000 Watts, the move to 1020 kHz did not turn out well. KYW had a problem with its signal. On November 11, 1928, the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) moved KYW to 1020 kHz – but the results were disastrous.

TRYING TO FIND A GOOD SPOT

After the move, there were parts of the region where listeners had trouble getting KYW clearly –including a “dead spot” on the north side of Chicago.

KYW resorted to installing a booster transmitter, KYWA, on the roof of the Edgewater Beach Hotel, but it did not solve the entire problem. One critic described the signal as “distorted mushiness,” especially at night.

In the summer of 1929, KYW asked the FRC for permission to move its main transmitter from the top of the Congress Hotel on Michigan Avenue in downtown Chicago out to a suburban location. It also asked for a power boost from 10,000 Watts to 50,000 Watts.

A possible complication was FRC Rules: in early 1927, the newly-created FRC had divided the United States into five geographic zones, and the commissioners were concerned about limiting the number of high powered stations in each zone. There were already quite a few 50,000 Watt stations in Zone 4, so the FRC found a way around the limitations by allowing KYW to use a cleared channel allocated to Zone 2, even though geographically, KYW was in Zone 4.

COMPLICATIONS

Once the FRC gave the okay, the Westinghouse engineering staff began construction of KYW’s new, state-of-the art transmitter in mid-summer 1929, at a cost of about $250,000, (about $5.5 million in today’s dollars), with an expectation of being operational by the end of the year.

Construction of KYW’s new transmitter took a little longer than expected, because finding the right location required some additional time. Westinghouse first looked at Addison, Illinois, about 22 miles from Chicago, and finally decided on Glen Ellyn, about 25 miles away. Experimental tests began in mid-January 1930, and they went well.

On February 1, 1930, the station’s new “super-power” 50,000 Watt transmitter was officially put into use. The inaugural broadcast received lots of newspaper coverage – and not just because 50,000 Watt stations were still the exception rather than the norm. The other reason for covering the official launch was that KYW treated the event like a momentous occasion. The station broadcast a special night of celebration that lasted from 10 PM to 4 AM, with numerous local entertainers taking part. There was a symphony orchestra, a 40-member chorale group, and greetings from various dignitaries.

While the KYW publicity department proved once again that it could get an impressive amount of publicity, the engineers were waiting to find out if the public was happy with the station’s new and improved signal. And in reality, while the transmitter was indeed capable of 50,000 Watts, the FRC was still concerned about too many high-powered stations in one region, so KYW agreed to operate with 10,000, rather than 50,000 Watts for the foreseeable future. But the new transmitter was a major improvement and most listeners probably thought they were listening to a 50,000 watt station.

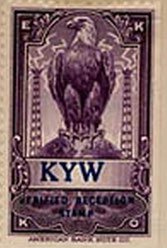

KYW Chicago

Reception Verification Stamp

American Bank Note Co.

Meanwhile, some other stations that did not get permission to boost their power were not happy about it, and they let the FRC know. Also unhappy were some of the smaller-market stations, who were opposed to the entire plan of letting certain stations have cleared channels and higher power – these smaller stations believed the higher-powered stations would drown out their signals or interfere with their coverage area.

Still, the FRC allowed the construction of some 50,000 Watt transmitters in certain cities to proceed.

LONG DISTANCE ISSUE

Some 760 miles away, in Philadelphia, events were taking place that would eventually affect KYW, although few people could have predicted it at the time.

It all started in 1924, when Dr. Leon Levy, a dentist, along with his brother Ike, a lawyer, purchased a then-small radio station: WCAU. The two gradually transformed WCAU into one of Philadelphia’s most influential stations, and it became one of the first two affiliates of the newly formed Columbia Broadcasting System (later known as CBS) in the autumn of 1927. Both Levy brothers were members of the group that acquired Columbia, as it was then called, in November, and they joined its board of directors.

Dr. Levy, who was named secretary-treasurer of Columbia, was also focused on WCAU, where he was the president of the station, and supervised its programming. And when the FRC opened up the possibility of higher-powered AM stations, he began advocating for WCAU to be one of them.

In mid-1928, WCAU was operating with 1000 Watts, but Dr. Levy soon received favorable news: in May 1929, the FRC gave him permission to boost WCAU to 10,000 Watts. And then, in mid-1930, Dr. Levy asked the FRC if WCAU could take the next step and operate at 50,000 Watts. (Interestingly, when the case came before the commission in September, one of the attorneys arguing on behalf of WCAU was Ike Levy.)

But this time, WCAU had competition: WCAU was in Zone 2, and was now competing with three other stations that wanted high-power too. Finally, in February 1931, the FRC’s chief examiner recommended that WCAU get the 50,000 Watts.

MOVE NUMBER ONE

Back in Chicago, even though KYW was using a Zone 2 allocation, Zone 4 still remained overcrowded, and Chicago had more 50,000 Watt stations than many other cities.

Ultimately, the FRC decided that the 1020 allocation from Zone 2, which they had agreed to let KYW use, needed to revert back to its intended use – a station that was actually located in Zone 2 should have it. And that meant if KYW wanted it, the station needed to move to a different city.

The FRC chose Philadelphia, a comparably-sized market in less-crowded Zone 2. KYW and Westinghouse did issue an objection to the ruling, but they seemed resigned to the fact that the FRC had the authority to move the station.

Trying to make the best of the situation, KYW continued broadcasting to its Chicago listeners, while plans were put in place to build a new transmitter in Whitemarsh Township, Pennsylvania (and a transmitter that would operate with 10,000 Watts); studios would be in Philadelphia, on Chestnut Street.

Chances were that KYW’s listeners had no idea conversations between KYW’s management and the FRC were taking place, and the official announcement that KYW would be moving was probably quite a surprise.

The notification about the move first appeared in the newspapers in late October 1933; but as radio magazines like Broadcasting showed, the FRC had been holding hearings with Westinghouse since July 1932. The new KYW would still be at 1020 kHz, but it would switch from NBC Blue to NBC Red (swapping affiliations with WFI).

And Dr. Leon Levy, who still ran WCAU, would now be the new president and general manager of Philadelphia’s newest station; in fact, KYW’s studios were in a building he owned.

THE SWITCH

And on Monday night, December 3, 1934, the new KYW made its debut in Philadelphia, with a five-hour special program, featuring more than fifty performers – including such big names as singer Jessica Dragonette, comedian Ed Wynn, and Paul Whiteman’s orchestra. Portions of the celebratory program were broadcast over NBC.

What was unique from a technical standpoint was that KYW broadcast from Chicago until the time for it to transfer its broadcasts to Philadelphia – which occurred seamlessly. The Chicago transmissions ceased and the Philadelphia transmissions began – and an era in Chicago broadcasting officially came to an end.

In Philadelphia, Dr. Levy did not make major changes in KYW’s programming. But he did offer several unique innovations that were rare for that time. We will talk more about that in the Sidebar.

BIG MANAGEMENT CHANGE

The next several years would bring other changes at the station. In July 1936, NBC announced it would take over the running of KYW.

When the station first went on the air, Westinghouse and NBC made an agreement with Dr. Levy to have him manage KYW. He knew the market, he knew radio, and he agreed to take on the job. But two years later, he wanted to return to managing WCAU only. In accordance with his wishes, NBC executives agreed to oversee KYW.

Vocalist and an orchestra leader Leslie Joy was named station manager. In mid-May 1938, KYW moved to its own larger and more modern studio complex on Walnut Street.

1940’s era

Philadelphia Reception stamp

But as it turns out, there were many more twists and turns to the story of KYW’s Philadelphia adventure,

FINALLY: 50,000 WATTS

In October 1940, KYW finally got approval from the FCC to go from 10,000 Watts to 50,000.

The 50,000 Watt signal went into effect on January 16, 1941, and to celebrate, KYW broadcast a special program, featuring greetings from former station personnel who now worked for NBC: among the voices the listeners heard were bandleader Jules Herbuveaux, and announcers Gene Rouse and Maurice Wetzel. KYW also debuted a new slogan: “KYW – Where You Hear the Stars,” a reference to famous performers on NBC Red like Jack Benny, Bing Crosby, George Burns & Gracie Allen, Eddie Cantor, and others.

To solidify the new location, KYW’s announcers saluted the cities in KYW’s new coverage map, and the station sent out a sound truck, decorated with the station logo, to drive to each community, playing transcriptions of popular KYW/NBC programs, and giving out promotional items.

A TINY MOVE AND THEN FM

In March 1941, as a result of the North American Regional Broadcasting Agreement (NARBA), the Federal Communications Commission relocated KYW to 1060 AM; that frequency is still KYW’s to this day.

In 1942, Westinghouse applied for an FM license for KYW. Leslie Joy, who was still the station’s General manager, helped to launch the new venture. At a time when FM was still considered an experiment and not many people owned the necessary receivers, KYW-FM debuted as the fifth FM station in Philadelphia with little fanfare, in mid-October 1942, as W57PH at 45.7 MHz.

Offering both popular music and classical programs the station was initially on the air for six hours a day – from 3-9 pm. But as a result of World War II, shortages of parts and materials were increasing – and manpower was becoming a problem too, since many men were being drafted.

TRYING TO SAVE THE FM

In some cities, owners were rethinking whether to keep their FM on the air – these stations were an expense, and finding ways to save money became crucial.

In Philadelphia, they kind of went Back to The Past. Remember when stations shared the day, even offering Silent Nights so listeners could hear other stations?

During the war years, rather than go dark, the Philadelphia FM operators came up with a plan where each of the stations would broadcast on alternating days. The station managers collaborated to select the program and music schedules, and they decided which day each station would get its turn on the air. They even helped each other with personnel or equipment when needed.

The plan worked. It provided each FM the opportunity to continue broadcasting, even on a limited basis.

HAVING TO LET GO

At first, Westinghouse had faith in FM’s future.

In September 1948, KYW-FM’s new 576-foot tower was completed; along with other equipment upgrades, the station would now have an effective radiated power of twenty kilowatts.

Unfortunately, interest in FM did not take off the way Westinghouse expected. By 1953, KYW-FM’s hours were reduced, and by mid-1954, the station had ceased to broadcast; Westinghouse donated it to the Delaware Valley Educational Television Corporation, which, along with the Philadelphia Board of Education, planned to operate an educational FM station.

Today, the former KYW-FM is WHYY 90.9 in Philadelphia.

RADIO AND TV PROMPT A MOVE

Programming-wise, KYW continued to rely on NBC’s network shows, many of which were still very popular.

But while AM continued to hold on during the late 1940s, it was beginning to lose some of its audience to television. To make sure it remained competitive, Westinghouse purchased Philadelphia’s channel 3, WPTZ, from the Philco Corporation in late February 1953.

The biggest change of all occurred in May 1955, although “well founded rumors” began circulating as far back as January that NBC and Westinghouse were negotiating a swap “between their Philadelphia and Cleveland broadcasting properties.” NBC and Westinghouse had reached an agreement to trade TV properties, with Westinghouse swapping channel 3 in Philadelphia, WPTZ, for NBC’s Cleveland outlet, WNBK, also on channel 3 – which would give NBC a property near parent company RCA’s manufacturing plant in Camden, New Jersey. NBC also agreed to pay Westinghouse $3 Million.

Of course, the FCC had to approve the swap, but given the two powerful companies involved, there were few who thought the deal would be stopped.

TROUBLE BREWING

In late December 1955, by a 6-1 vote, the FCC allowed the deal to go through. KYW was to move 430 miles to the Northwest.

When the switch officially took place, KYW was able to keep its heritage call letters, replacing what had been WTAM since September 1923, but it still had to use WTAM’s frequency – 1100 on the AM dial. And the Cleveland TV station was no longer called WNBK – it was now KYW-TV.

But the one dissenting commissioner, Robert T. Bartley, wondered whether rumors he had heard were true. According to these rumors, Westinghouse was threatened with the loss of their NBC affiliation if they did not agree to the deal. Bartley asked in his dissent whether this possibility had been thoroughly investigated.

The commission simply had sent a letter to NBC, asking if there was any truth to it, and when NBC said there was not, no further inquiries took place. Still, Bartley said he found that the entire transaction raised “disturbing and unanswered questions.” And these questions did not go away, even after the swap had been completed.

LIFE IN CLEVELAND

KYW announced it would keep its NBC network programs, and the station also kept some of the former WTAM on-air staff, although sometimes in different shifts.

For example, afternoon host Bill Mayer now hosted the morning show. Another holdover was popular women’s show host Mildred Funnell, who had joined WTAM in 1930. She and her colleague Gloria Brown had been in charge of the “Women’s Club of the Air” since 1950, and they now did their show for KYW weekday mornings at 9:30. In addition to the NBC shows, KYW now had an evening classical music and light opera program, a late-night jazz show, and some radio plays, as well as local news, and several new educational features.

By 1959, KYW had gradually evolved into a pop-music station with personality disc jockeys, and more station promotions and contests. Unfortunately, this proved problematic; when the payola scandal broke into the news in late 1959, KYW was among the stations affected. In early December, Westinghouse announced the firing of two of KYW’s deejays, Joe Finan and Wes Hopkins, for accepting money from record companies. Over the next several years, KYW sometimes struggled to find a musical identity, moving back to a more middle-of-the-road sound, but then, gradually returning to pop music again.

THE TROUBLE GROWS

However, while KYW in Cleveland and WRCV in Philadelphia were trying to settle in, those questions FCC commissioner Bartley had asked were now being asked by the US Justice Department, which was looking into possible antitrust violations.

Drew Pearson, a widely syndicated newspaper commentator, was covering this extensively during 1956. In one column, he suggested that David Sarnoff, the powerful and influential president of NBC and RCA, had friends in high places (including US Presidents from both parties and the current head of the FCC), and he was thus able to persuade the FCC to expedite the deal, without even so much as a hearing. Pearson believed the Justice Department investigations of how the swap came to fruition were warranted, and even though the deal had gone through, he was certain the investigations of it would continue.

Pearson’s assessment turned out to be accurate.

INTO LEGAL TROUBLE

While the Justice Department continued looking into the situation, a House of Representatives antitrust committee was investigating the swap and the FCC’s willingness to approve it.

In the Federal District Court in Philadelphia, a civil court action was filed by US Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr., focusing on whether NBC and RCA had “unlawfully conspired” to acquire ownership of television stations, using their power to “grant or withhold NBC network affiliation” unless they got the deals they wanted. The suit said the NBC-Westinghouse swap should therefore be declared unlawful and NBC should be ordered to divest from the properties it had acquired coercively.

A district judge dismissed the suit, ruling it had been filed too late, and that the FCC should be the primary decision-maker about these matters. Justice appealed, and in February 1959, the Supreme Court reversed the district court, saying the Justice Department’s case could go forward. That was the result the Justice Department wanted, as they remained concerned about NBC now owning TV stations in five of the nation’s largest markets. By September 1959, NBC had reluctantly entered into a consent decree with the Justice Department, agreeing to divest from one of those markets – Philadelphia – by December 31, 1962.

But that did not happen.

MORE AND MORE CONVOLUTED

In fact, in early 1960, NBC asked the FCC to approve yet another station swap, and this one was bigger than the controversial Cleveland and Philadelphia deal.

Now, NBC wanted to swap its radio and TV stations in Philly for WNAC Radio and TV and WRKO-FM, the Boston outlets owned by RKO General. It also wanted to sell its Washington DC properties, WRC-AM and WRC-TV, to RKO General. And it wanted to buy KTVU-TV in San Francisco/Oakland.

Westinghouse’s management was not happy about any of this. They worried that these proposed moves could jeopardize their NBC affiliation in Boston (where they owned WBZ-TV and radio), and they wanted to resume operation of the Philadelphia properties they lost. But it did not seem like there was much they could do to stop the deals, which got the okay from the Justice Department in late May 1960, and it seemed the FCC would go along with it too, despite Westinghouse’s objections.

However, just like it took nearly three years for an order telling NBC to divest from ownership in Philadelphia, acceptance of NBC’s proposal did not happen right away either.

MORE CHEFS IN THE KITCHEN

In fact, several parties, including Westinghouse, and television manufacturer Philco, the original owner of WPTZ (now WRCV-TV) in Philadelphia, were letting the FCC know of their concerns.

Westinghouse, of course, wanted to be back on the air in Philadelphia and expected the FCC to hold NBC to the terms of the consent decree. But Philco, by now owned by the Ford Motor Company, wanted to return to having a Philadelphia television property; and Philco had long disagreed with the idea that Westinghouse should be awarded channel 3. So, in 1960, Philco filed an application challenging NBC’s Philadelphia television license, accusing NBC of “anti-competitive practices” that made the company unfit to own and operate broadcast properties.

Hearings finally took place in late October 1962, but unfortunately for Philco, the FCC ruled against them in the summer of 1964.

WESTINGHOUSE WINS, MOVES AGAIN

But the good news for Westinghouse was that the commission seemed to have reconsidered its ruling from back in 1955.

In an unexpected 5-0 decision, one that surprised the reporters who had covered the nine-year battle between NBC and Westinghouse, the FCC reversed itself, explaining in a strongly-worded statement that it had uncovered conclusive evidence proving NBC had used “coercive and inequitable” tactics when it obtained the Westinghouse stations in Philadelphia.

Given these new facts, the commissioners decided the only way to make things right was to undo the swap and return the Philadelphia properties to Westinghouse.

AND MOVE IT DID

It was undoubtedly confusing for Cleveland radio listeners on Saturday June 19, 1965.

KYW in Cleveland had become a popular Top-40 station, with Jerry G and Jim Stagg among the top deejays in the city. WRCV in Philadelphia was playing adult-contemporary, along with sports, news, and local features. Now, Cleveland listeners would be hearing the hits on WKYC, and Philadelphia listeners would be hearing the softer sounds on KYW.

But while WKYC continued with Top-40, KYW soon changed its format. In New York, another Westinghouse station, WINS, had been airing an all-news format since April. This was something new and innovative at that time; since it was getting good response in New York, Westinghouse decided to bring the format to Philadelphia.

ALL NEWS ALL THE TIME

On September 21, 1965, KYW Radio began broadcasting “All News All the Time,” making it possible for listeners to “get the news the minute they want it.”

Westinghouse’s management was hopeful that this new format would be a winner, since what the former WRCV had been broadcasting was “low rated, and economically operating at a loss,” according to Group W president Donald McGannon. At first, critics wondered if there would be enough interest to support a 24-hour all-news operation, but it turned out to be a brilliant move – the audience continued to grow, and by the early 1970s, KYW had the top ratings in the city. According to Arbitron ratings, more than 1.4 million people were tuning in every week.

The station also became a reliable resource for weather and traffic reports. And while many other formats came and went from AM radio, all-news proved remarkably durable.

The transmitter location, just NW outside the city on Joshua Road in Lafayette Hill is a neatly maintained site with the two tower directional array putting out a strong 50 kW signal to the Northwest and Southeast.

In December 1986, KYW began AM Stereo broadcasting using the C-QUAM system, and added the phrase “in AM stereo” to their top of the hour ID. The phrase was discontinued in the late 1990s and the C-QUAM AM stereo was abandoned in 1998.

Currently, KYW continues as a 50 kW DA-1 on 1060, and is simulcast on 94.1 FM HD-2 and 103.9 FM in Jenkintown PA.

A CENTURY OF BROADCASTING

A lot has changed in broadcasting since KYW debuted in 1921, yet one thing has not changed: this is a radio station with amazing longevity with a special call: KYW is the easternmost station in the United States whose call sign begins with the letter K.

From its early days in Chicago to its relocation to Philadelphia and then to Cleveland and then back to Philadelphia, KYW has had a fascinating history. Many of its announcers and reporters have had long careers in broadcasting; a few even became nationally known, among them NBC’s Andrea Mitchell, who spent nearly a decade at KYW, covering city hall as one of the station’s first full-time newswomen.

Today, KYW is owned by Audacy (formerly Entercom). It broadcasts from studios at 400 Market Street in Center City. And while its ratings are not as robust as they were in past decades (a fact of life for most AM stations), KYW remains an important part of Philadelphia, as it has been for so many years.

– – –

Donna L. Halper is a media historian, educator (Associate Professor of Communications and Media Studies at Lesley University), and radio consultant.

She is the author of six books and many articles about the history of broadcasting. Contact her at: dlh@donnahalper.com

– – –

Did you enjoy this article? Would you like to know when more articles like this are posted? It only takes 30 seconds to sign up here for the one-time-a-week BDR Newsletter.