Centenary Radio: WBZ Crosses The 100-Year Line

[September 2021] With its first broadcast on September 19, 1921, WBZ was one of the first of what would become a flood of new “commercial” wireless stations licensed by the US Department of Commerce (DoC). To mark WBZ’s 100th Anniversary, we kick off a series of historical looks at how the earliest stations have fared over the past 100 years.

Whenever discussing the history of broadcasting, the question asked most often is “Who was first?”

Nevertheless, this is not an easy question to answer. For the first decade, there really were few differences between broadcast stations, amateur stations, so-called “special land stations,” and experimental stations, just to name a few. Usually they were more concerned with just getting on the air – and staying on the air!

First you have to define “First what?”

Radiotel-ephone transmissions date back to 1906. The Radio Act of 1912 inaugurated the licensing system here in the US. Early commercial broad-casting essentially was by radiotelegraph stations, sending and receiving messages, sent for a fee. “Regular programming” as we might call it also dates to the same time period.

With this in mind, identifying claims of “Who was first?” requires careful research. One narrative you might find useful is here. The reader will see how difficult it is to truly arbitrate who and what was “first” all these years later.

One thing we do know for sure is that when the DoC specifically started issuing licenses to stations wishing to provide programming for listeners, WBZ received licensed #224 on September 15, 1921. And while this station, operated by the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company started programming almost immediately on September 19th, 1921, there already was broadcasting on the air in the area coming from 1XE in Medford Hillside, MA.

WBZ STARTS MAKING WAVES

The new station was located in East Springfield MA, at the Westinghouse plant on Page Boulevard. Its call sign, WBZ, was reused – it had previously been the call of the ship Santa Elana, which burned off the coast of Peru on July 26, 1920.

As mentioned, WBZ went on the air September 19, 1921. Its first broadcast actually was what we today would call a “remote,” from the Eastern States Exposition, a major regional agricultural fair. Among the speakers who helped to dedicate the station were the governors of Connecticut (Everett Lake) and Massachusetts (Channing Cox).

As with all the commercial broadcasters, WBZ signed on at the new frequency assigned by the DoC to all broadcasters – 833 kilocycles (now, kilohertz). The first transmitter ran 100 Watts.

Within several years, the station would move to 900 kHz, and by 1928 it was placed at 990 kHz by the Federal Radio Commission. Its power also increased (it ran 2000 Watts by 1925), and listeners in other states began reporting that they could hear WBZ’s signal.

Interestingly, while the debut of this new radio station was big news in Western Massachusetts, the local Boston newspapers seemed somewhat less than impressed. Seeing radio as the competition, they buried the story on the inside pages. But gradually, as interest in WBZ grew, print reporters found they had no choice but to expand their coverage of broadcasting, and by 1922-1923, WBZ received much more attention.

BETTER DIGS

The original studios at 655 Page Boulevard were on the roof of the Westinghouse factory. As in most early stations the studio and transmitter shack were essentially the same room. Lean back a little bit too far, and you would touch the transmitter wiring!

The original 1921 WBZ studio at Page Boulevard

It did not take long before Westinghouse saw the need to have a more comfortable studio. Asking famous stars like opera singer Madame Louise Homer to come to the plant and step over lots of wires and pieces of equipment just did not provide the kind of image the station wanted to project.

In early 1922, therefore, WBZ opened a new and more aesthetically pleasing) studio in East Springfield’s Hotel Kimball. The studio was further modernized in 1924.

ON THE AIR

If you had listened back then, you would have found the programming typical of radio in those pioneering days: an occasional star (such as Madame Homer) but mostly eager local musicians willing to perform for free.

Westinghouse management was right, people were listening. However, although some of the locals were actually quite talented, East Springfield MA was not a central location for the biggest names, most of whom performed in Boston, about ninety miles away. By early 1924, with many more stations on the air, competing for the performers’ services, it was becoming difficult to get the kind of talent Westinghouse sought.

To solve the problem, Westinghouse decided in late February 1924 to open a Boston studio and transmitter site, in conjunction with the Boston Herald-Traveler newspapers, from which they got their news at that time.

EXPANDING REACH AND CONTENT

The new station was assigned the call letters WBZA and it was essentially operated as a simulcast of WBZ. Together, the stations pioneered the new medium.

WBZA’s first studios were in Boston’s Hotel Brunswick. Soon, broadcasting from a hotel became common, as hotels provided large ballrooms for dancing, as well as a house orchestra. WBZA’s Boston studio made use of popular bandleader Leo Reisman and his Hotel Brunswick Orchestra. Over the years, the studio moved to the Statler Hotel, then the Bradford.

Not only was the new location’s ability to attract major talent – a big plus for Westinghouse – but its proximity to the Boston sports scene was also helpful in attracting new listeners. WBZ was the first station to broadcast Boston Bruins hockey games (featuring Herald sportswriter Frank Ryan doing play by play), beginning in December 1924. And in April 1925, WBZ broadcast a Boston Braves baseball game, complete with player interviews.

WBZ also became known for broadcasting big news events: the station broadcast the inauguration of President Coolidge in 1925 and, in 1929, WBZ was the first station to broadcast the inauguration of a governor (Frank G. Allen) from the State House in Boston.

When not doing sports, the station provided a regular schedule of dance bands, well-known singers, political talks, a story teller for kids, and a staff of announcers who became very popular in their own right.

One Springfield-based program which earned considerable respect was a children’s program hosted by author and naturalist Thornton W. Burgess. Burgess taught kids and their parents to appreciate and conserve nature, and he was the subject of a number of positive articles in newspapers all over the eastern United States.

TRADING PLACES

While the original plan had been to focus on East Springfield and then offer some big names from Boston, it did not take long for the Boston studio to increase in importance.

The Springfield studios did provide some of programming during the 1920s (and amazed listeners with the “magical” ability to switch between Boston and East Springfield almost instantaneously), but it was becoming more apparent that the Boston studio was what brought in most of the listeners, thanks to a continuous parade of big-name celebrities, political figures, and sporting events. (WBZ was also able to affiliate with a national network, becoming one of five original stations of NBC Blue, which gave the station further access to major talent.)

By February 1931, Westinghouse finally decided it was time to flip the call letters to reflect the reality that most of the programming now came from Boston. WBZ became the name of the Boston station and WBZA transferred out to East Springfield.

GROWING PAINS

One issue, over time, started to cause WBZ’s relationship with NBC Blue to grow just a bit rocky.

While Westinghouse was pleased with the programs the network offered, a number of WBZ’s best announcers (including John Shaw Young and Alwyn Bach) were hired away by the network. On the other hand, when WBZ had its tenth anniversary celebration in September of 1931, NBC Blue carried part of it, spreading WBZ’s fame to a national audience.

Unfortunately, some of the news about WBZ in the early 1930s was not entirely positive. In late 1931, Program Director John Clark launched a “purity campaign,” wherein he threatened to ban any songs with what he felt were risqué lyrics.

This caused a very public argument with popular bandleader Joe Rines, who was not amused when Clark cut off a Rines broadcast in mid-song because Clark felt the lyrics were offensive. Newspapers and magazines immediately took sides, and a debate about the policy ensued for several weeks.

Then, in April of 1932, WBZ got another rather dubious bit of publicity, which showed the perils of live radio. King Leo, a supposedly tame circus lion (he was trained to roar on cue) was brought to the studio.

Springfield (MA) Republican headline – April 29, 1932

For some unknown reason, King Leo broke away, rampaging through the studios, breaking glass, destroying equipment, terrifying spectators, and injuring seven people before the police arrived and shot him with a tranquilizer gun.

Fortunately, most of what WBZ provided was well-received and much appreciated, especially its weather forecasts by meteorologist G. Harold Noyes from the Massachusetts Weather Bureau. The station became known for its live coverage of natural disasters like floods or hurricanes.

The news department made news itself in 1939, when WBZ was first on the scene when the U.S. Submarine Squalus sunk off the coast of Portsmouth NH.

WBZ Newsroom during Squalus coverage

WBZ also fed the NBC radio network, as listeners waited to find out if any of the men would be rescued (sadly, 26 of the 59 sailors drowned).

CRANKING UP THE POWER

WBZ began running 50,000 Watts in 1933, from a powerful new transmitter in Millis, MA. Along with many other clear channel stations, WBZ then applied for a license to run 500 kW, just like WLW in Cincinnati. However, the application was withdrawn soon after, as it appeared to be politically impossible to win FCC approval.

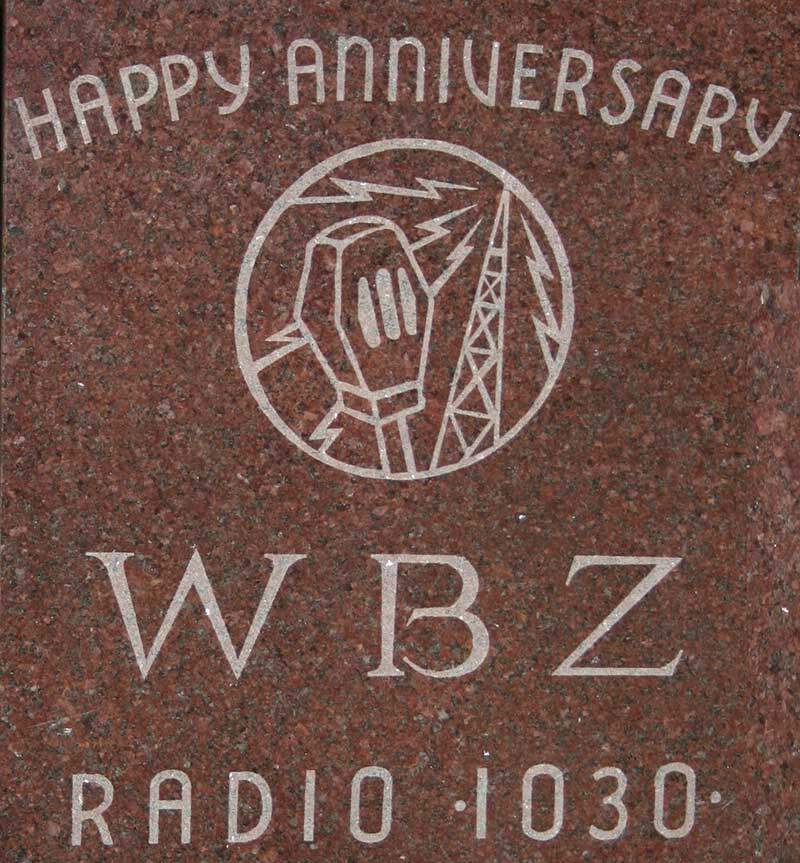

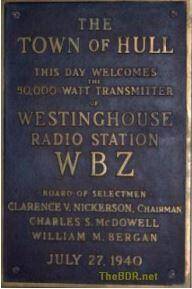

Instead, during 1940 WBZ moved their transmission site to Hull, MA and installed a Westinghouse 50HG 50 kilowatt feeding directional antenna with two half-wave towers to redirect the power radiating over the Atlantic back to the West, increasing the station’s coverage, reaching well over 30 states at night. Also, in accord with the North American Radio Broadcasting Agreement (NARBA) the station moved from 990 to 1030 kHz, the dial position it still has today.

With its two half-wave towers,

WBZ throws most of its 50 kW to the West

WBZ’s Transmitter building in Hull, MA

The transmitter building blends right into the neighbor-hood – it is only the two towers that tell what is going on inside.

A wall plaque at the Hull site

The elevated tower bases and walkways

keep the tidal waters well below the tower bases

GREAT COVERAGE SPARKS VARIETY

During the late 30s, WBZ had begun doing a morning show featuring nationally-known country vocalist Bradley Kincaid.

Although country and western (or “hillbilly” music) was not generally a big hit in Boston, given the large reach of the 50 kW, several performers did very well there – Kincaid was one.

Another was a local star, Georgia Mae, who became famous for her ability to yodel as well her skillful singing and playing.

In 1942, Carl deSuze joined the station and he would go on to a long career as the morning show host. The programming in the 30s and 40s also included a daily women’s show (radio homemakers were very popular, and WBZ had Mildred Carlson and, later, Marjorie Mills).

FM AND TV, TOO

Experiments with FM began taking place in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

WBZ used its FM (W1XK) to broadcast the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1941, probably the first time the BSO had been heard via the new FM technology.

After years in downtown Boston at area hotels WBZ radio (AM and FM) were joined by WBZTV (Ch. 4 – Boston’s first TV station) in June of 1948 as they moved into their own new facility, which had been specially designed for both radio and TV. It was located on Soldiers Field Road in Brighton, a neighborhood not far from Boston proper.

In the mid-1950s, WBZ underwent a major change, as a new kind of music (top 40) became popular. The station moved away from its previously “middle-of-the-road” programming in the summer of 1956, dropping NBC and abandoned big bands for a more “hit-oriented” sound (although out west in East Springfield WBZA continued as usual during the daytime).

The station hired five well-known announcers and called them “The Live Five” to promote the format and to let the audience know WBZ was now locally programmed. Yet, while WBZ did play the hits, its music could really be considered soft-Top-40 (what used to be called “chicken rock”).

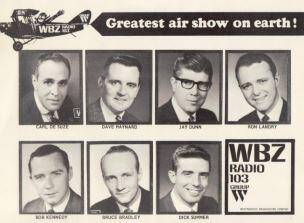

By the 1960s, WBZ was competing with other Top-40 stations on the strength of such highly-rated personality disc jockeys as Bruce Bradley, Dave Maynard, and Dick Summer. (Summer’s quirky overnight program was a big hit with insomniacs and college students.) Bradley and Maynard made a number of appearances at record hops and at remote broadcasts.

A WBZ promotional ad from the mid-1960s

Nevertheless, WBZ did not entirely stray from its former middle-of-the-roads roots. Jefferson Kaye did a folk music program called “Hootenanny” which was very popular in Boston and nearby Cambridge, where some of the up-and-coming folk stars performed. And the station still offered a nightly talk show (Bob Kennedy’s “Contact”) along with a heavy news commitment.

BACK TO FULL SERVICE

Entering the 1970s, WBZ moved itself back from Top-40 to a more adult-contemporary sound, and increased its news coverage.

The station had introduced a call-in sports talk show, “Calling All Sports” with Guy Mainella, in the summer of 1969, and sports coverage was an important part of the broadcast day as well.

Gil Santos began doing play-by-play of Patriots football on WBZ in 1966; he became WBZ’s morning sports anchor in 1971, a position he held until he retired from doing morning sports in 2009.

Meanwhile, WBZ long known for public service, increased its efforts to raise money for such worthy charities as the Salvation Army, Red Cross, and Boston’s Children’s Hospital.

TALK TO US

In the 1980s, music was gradually being phased out all-together in favor of longer news blocks, more sports, and more talk shows.

By December of 1985, WBZ was fully converted to All-News and Information in afternoon drive. The station completed the transition to an All-News station in September of 1992, with talk shows at night.

Among them was Talk Radio legend David Brudnoy, one of Boston’s most highly-rated talk hosts.

David Brudnoy circa 1988

A libertarian conservative, known for his erudition and his courtesy to even those guests who did not share his views, Brudnoy’s evening talk show was heard and enjoyed in more than 30 states, thanks to WBZ’s strong signal.

GOODBYE EAST SPRINGFIELD

Ironically, the city where everything began for WBZ – East Springfield – was no longer a part of the WBZ game plan after 1962.

First, WBZA was shut down by the parent company, in order to buy another station in a larger market.

Later on, 2011, the factory site was sold and the original towers were brought down. Today, the old Westinghouse office building is the only thing on the large site, awaiting re-development.

The original WBZ/WBZA towers were at

the East Springfield Site until removed in 2011

However, a final send-off for WBZA occurred when WBZ celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1971. As a tribute to the station’s beginnings, festivities were held both in Boston and out at the Eastern States Exposition in Springfield. The towers continued to sit in place for at least the next 40 years.

Meanwhile, out at Hull, the old Westinghouse transmitter had been replaced by a Harris MW-50, then a DX-50. Today the DX-50 and a Harris 3DX50 share as alternate main transmitters, with the programming also transmitted on an HD-2 channel of co-owned WXKS-FM.

Another change: WBZ is no longer identified as a Westinghouse station. Westinghouse bought CBS in 1995 and in 2000 the corporate name was changed to CBS. Although the name and circle logo are still owned, the historic Westinghouse name was no longer used.

Still more change occurred in 2017 when CBS merged with Entercom and divested a number of stations, with iHeartMedia purchasing WBZ. The Soldier Field Studios were abandoned in favor of consolidating WBZ’s studios with the other iHeart stations in Medford.

A WELCOME NEIGHBOR

WBZ is one of the few pioneer stations that still uses its original set of call letters, 100 years later, through all the changes in ownership, staff, and power.

But some things did not change.

A 1930’s Ekko Stamp

The station long had a stable staff the listeners could count on year after year. In addition to the 38 years that Gil Santos was with WBZ, other staff members had great longevity as well. For example, both Carl deSuze and Dave Maynard retired after more than forty years on air.

In recent years, the consolidation and changes in broadcast operations have brought a number of changes, but WBZ Radio has won numerous awards for public service and excellence in broadcasting, including the National Association of Broadcasters’ Crystal Award and the Marconi Award. In 2010, WBZ earned an NAB Marconi Award for being radio’s Legendary Station of the Year. In 2014, WBZ received a Peabody Award for coverage of the Boston Marathon bombing. In 2016 and 2017 Edward R. Murrow Awards were added.

Today, as throughout its history, WBZ continues to cover local news, and it still provides live and local talk shows.

Furthermore, despite the fact that some AM stations have seen dramatic losses in listenership, WBZ has consistently continued to be in the top three in the Boston market ratings.

In 2021 WBZ as celebrates its 100th year on the air, its long history as a pioneering station continues to make a difference in the community and in the lives of its listeners.

– – –

Donna L. Halper is a media historian, educator (Associate Professor at Communications and Media Studies at Lesley University), and radio consultant. She is the author of six books and many articles about the history of broadcasting. Contact her at: dlh@donnahalper.com

– – –

Did you enjoy this article? Would you like to know when more articles like this are posted? It only takes 30 seconds to sign up here for the one-time-a-week BDR Newsletter.