Contract Engineering: The View from the Client’s Side

[January 2011] Contract engineering is a great way to build a business when no one station can afford to pay what a fulltime engineer is worth. It also gives great flexibility in terms of working hours. However, a contractor is not the boss – he works for someone. A successful contractor considers what his work looks like in the eyes of the client. Sam Wallington helps identify what the client is expecting to see.

After spending a few years working for a single station, I joined an engineering firm. We spent a number of years contracting in small, medium, and large market stations, providing everything from occasional vacation coverage for the regular engineer, to full-time coverage, and all the way up to “everything engineering,” including new signal and upgrade construction.

For the last 18 years, I have been on the other side of the desk, so to speak, engaging contract engineers all over the country. This last role, in particular, has given me the opportunity to see a large number of both brilliant and not-so-brilliant examples of contract engineering.

Looking from the Other Side

Most contract engineering articles tend to focus on the business aspects: Making sure you are properly licensed and insured, that you have a good business plan and charge appropriately, that you handle taxes properly, and so on. Occasionally, more technical articles come along which address some of the unique technical challenges of being a contractor.

However, I want to focus here on improving your craft beyond the technical or legal, looking more at what your client needs (beyond just getting them back on the air quickly).

As a client who has hired many contractors over the years, I have developed my own list of things for which I watch. How a contactor measures up to my list determines, to a large degree, whether I will hire him again – and what kind of recommendation I will give to others who ask about his services.

Though these pointers are primarily directed at contract engineers, staff engineers may also benefit. Some are easy to implement – and some take a lifetime. But all of these pointers should give you some ideas as to how to better serve both your clients (or employer) and your personal needs.

Tell the Truth

The first and foremost criteria for me is honesty. I cannot count how many times a contractor has bent the truth with me – or just outright told me plain lies.

Sometimes, it is because they think I will not understand them. But too often they just are trying to cover up the fact that they do not know the answer – or worse, they are trying to cover over a mistake they had made.

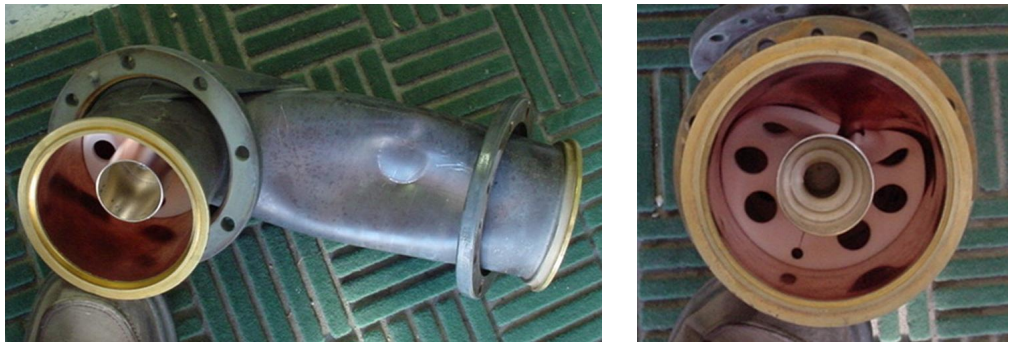

This elbow was damaged when a crew working for a co-located station dropped a 10-foot piece of conduit on it – and was then ready to leave the site without telling anyone. Photos: Gary Peterson

I will almost always find out the truth eventually – and when I do, the contractor drops considerably in my opinion and I am far less likely to ask them to work with me in the future.

If you do not know, say, “I don’t know, but I’ll find out.” If you make a mistake, even one that costs your client money, say, “I am sorry. I blew up the transmitter because I used the wrong part. I’ll make it right, and I won’t charge you for it.”

Yes, some folks will fire you on the spot – but many or most will recognize that your honesty is worth more than the mistake cost. In the long run, you will gain far more than you will lose.

Do the Job, But Do More Than Just the Job

Many contract engineers seem miss out on huge opportunities by failing to look around a site as they work. And it really annoys me when they are on site and miss something that could cost me off-air time.

If you are called to fix a problem, fix the problem. Then take a few minutes and look around. Probably there are likely a few (or a few hundred) other needs that could use your attention, ranging from minor (the transmitter site is a little dirty) to significant ones (the bottom bay of the antenna is damaged).

As you inspect, ask yourself these questions:

- What preventable thing might have caused the problem I came to fix?

- What else needs fixing here?

- Is there a need that no one has mentioned to you?

Do not be afraid to ask for more work. If you do not mention a problem to your client and offer to fix it, it is unlikely that you will be offered the opportunity (at least until it takes them off the air at 3 o’clock in the morning).

Usually just a brief mention, such as “Hey, I noticed that most of the lights are out on the console. I can fix that for you if you’d like” (although that one is simple enough you may just want to fix it as a “freebie” to build good will) is sufficient to get you some extra work.

Sometimes you may want to provide a formal quote. Your client can always refuse but it is important that they know what is happening – especially at remote transmitter sites. Besides, I suspect you would like to have some additional money.

The bottom line: this is a good way you can earn both your client’s trust and more income – usually with work that can be planned in advance instead of interrupting your dinner with a crisis.

Bring Tools and Some Basic Parts

Here is another common contractor weakness that surprises me: Many engineers do not have any tools with which to practice their trade.

Once when I was a contract engineer we acquired a new station as a client. I went out to visit and do an inspection.

When I walked in with my toolbox to see how much I could fix on my first visit, the GM looked at me in shock and asked what I was carrying. When I told him it was my toolbox, the GM shared that the previous “engineer” did not have his own tools, borrowing from the station instead – or just said he could not fix something.

Talk about giving your client a good excuse to look for someone else!

Besides that issue, as a contractor the IRS is expecting you to provide your own tools (among other requirements which you really need to know).

Your tools do not have to be expensive, but they are essential. To look at least minimally professional, be sure your tool kit includes:

- screwdrivers and Allen keys

- basic wrenches and sockets

- pliers and wire cutters

- soldering iron and solder

- flashlight (and spare batteries)

- a Volt-Ohm meter

As you grow your business, invest in more tools and test equipment so that you can be better prepared to serve your client’s needs. Some test gear is expensive, so know how and where to rent it – and pass the costs through to your client as needed for those special jobs.

Basic parts also include a small collection of “typical” resistors, capacitors, etc. And do not forget to carry a variety of fresh batteries – both for your flashlight and test gear, and for the stuff your clients use.

Hold the Complaints

Are you professional or not? Many brilliant engineers never get – or keep – the clients because they never learn how to control their attitude. That shows up as a tendency to complain (or in a myriad of other ways, such as how you dress).

Unless your client has become good friends with you, they really do not want to hear your problems:

- how bad things are

- how much you hate doing whatever job they have asked you to do

- how dumb the manufacturer of their equipment is that

- they got you out of bed, interrupted your meal, or otherwise inconvenienced you

- that you had no clean clothes

It is not that they are uncaring, but they would not have called if it was not reasonably important (and even if they did, it is their money that you are taking). Those torn jeans do not make a good impression unless you just tore them fixing their equipment.

If you do not enjoy what you are doing, perhaps you should be doing something else.

Instead, find the bright side as often as possible, and talk about that. Be cheerful. Be someone that is fun to have around. Let the difficulty of the job be a motivator, and show your client how you can remain upbeat. They will not forget:

- your smile

- your positive approach: “Let’s get this fixed for you!”

- your professional appearance.

- that you treated everyone with courtesy and respect.

- your laughing off the mud you have waded through to get to their tower

Really, this does tell a lot about your attitude. Operate positively, and there is a good chance they will try to do something to make it up to you – like giving you more business in the future.

Why Are You Here?

These are some of the building blocks that will lead to a great list of clients who will not only hire you regularly, but perhaps will begin to recommend you to other broadcasters when they start talking about the problems with their own engineer.

Next time, I will go a little deeper into this issue of attitude – and a few other helpful tips to make your contact engineering business successful.

– – –

Sam Wallington is the Vice President of Engineering for Educational Media Foundation in Rocklin (Sacramento), CA. You can email Sam at: swallington@kloveair1.com