John R. Brinkley: Early Radio’s Most Famous Fake

[September 2013] In many ways, the first decades of broadcasting were as if a Wild West. Stations competed a single frequency at first, using a quest for ever escalating power to overcome other stations. And some of the personalities who learned how to use radio to enrich themselves climbed on board with zest.

In this look at John R. Binkley, Donna Halper looks at one of the most famous radio entrepreneurs, the fantastic story he told, and the road to riches, then bankruptcy and an early death.

It was not P.T. Barnum that said “there’s a sucker born every minute.” The famous quote attributed to him actually was said by a competitor of his in 1869. But regardless of whoever really said it, those words can certainly be applied to the first decade of broadcasting.

A Quick Deterioration

Even though radio was new and regulators were trying to keep up, the majority of 1920s radio programs were honest and informative. They brought listeners up-to-the-minute news and weather, church and synagogue services for shut-ins, even concerts from the most famous performers.

But increasingly, radio also became home to a variety of quacks, fakes, and charlatans.

In the midst of the educators, news reporters, comedians, and opera singers, there were a growing number of mind-readers, mediums, faith healers, and astrologers plying their craft on radio stations all over the United States.

Perhaps best known of all was a man who called himself “Doctor Brinkley.” He was not really a doctor, but that did not stop much of the public from believing everything he said. The result was not a great addition to radio’s reputation.

Strange Communicators

The famous author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle told a gathering in 1922 that he expected the spirits would soon be able to communicate with us by radio. A believer in psychic phenomena and the occult, he was not the only one to make this claim. Marconi himself had been trying to contact other planets since about 1920.

By early 1923, radio was reporting about a French pharmacist named Emile Coué, who believed all illnesses were caused by the mind.

Coué, whose catchphrase was “every day, in every way, I’m getting better and better,” did not speak on radio, but practitioners of his autosuggestion method did, telling the public how they could train themselves to overcome most ailments.

Even Stranger Communicators

Summer 1923 also brought people like Leona Lamar, “The Girl with the Thousand Eyes,” to radio. Appearing on WHN, New York, she claimed to be a mind-reader, astrologer, and mentalist, offering to answer any questions mailed to her by listeners.

WHN evidently with a fondness for mind-readers, also featured magician Joseph Dunninger, who claimed his “supernatural powers” could hypnotize his subjects using only radio waves. Dunninger predicted that hypnotism by radio would soon be used by doctors to perform surgery without anesthesia.

Long before Art Bell dominated night broadcasting in the US, a British psychic asserted in 1926 that he had received messages from Mars and, he told his audience, he was sending back messages to that distant planet’s residents. There were some skeptics, but many listeners stayed awake late into the night to find out if the psychic could really talk to the Martians, as they believed he could.

Over time, more and more alleged healers came to radio, each claiming they had a miracle cure for every problem from obesity to cancer. Some offered potions, some offered prayers, but all were adept at separating the public from their money.

No matter how many times government officials and actual physicians tried to warn the public, the popularity of these phony doctors seemed to grow.

“Doctor” Brinkley

And that brings us to John R. Brinkley. Born in North Carolina in July of 1885, it appears the “R” originally stood for Romulus, but was later changed to Richard.

All through his life, Brinkley wanted to impress people. It may have come out of his early childhood experiences; not only was he born in poverty, but there is evidence his parents were not married – which would have been considered shameful back then and might have gotten him teased by his peers.

Brinkley did attend college, although one we might call “non-traditional” – the Kansas City (KS) Eclectic Medical University. He got his degree in 1915.

Schools like KCEMU accepted a wide range of healing methods, many of which were considered totally unreliable by the medical establishment. Likely, Brinkley studied homeopathy, chiropractic, and various herbal methods for making patients feel better.

J.R. Brinkley

In time the school and others like it would be attacked by the medical establishment as little more than “diploma mills” where anyone could pay $500 and get credentials – which is essentially what John R. Brinkley did.

Nevertheless, he would always insist on being called “Doctor Brinkley,” despite never graduating nor attending any accredited medical school.

Yet his lack of a traditional scientific education did not stop him from claiming extra medical expertise. In fact, on the 1920 U.S. Census, he listed his occupation as “surgeon.”

Strange Surgery

Brinkley was best known for his “goat gland” surgery, which he began performing in cities like Chicago before setting up his own hospital and clinic in Milford, Kansas.

His assertion was that if goat glands were transplanted into a man’s scrotum, it would give the man extra virility and a longer life. The operation was available for “only” $750 (something close to $10,000 today), and Doctor Brinkley offered the media interviews with some men who supposedly had experienced wonderful results from the operation.

One problem: there was no objective proof that goat gland surgery worked.

When organizations like the American Medical Association heard about it, they were horrified. As early as August 1920 a group of Chicago physicians, including the director of the Illinois Red Cross and the former head of the Chicago Medical Society, told the media that such an operation was nonsense; not only could it be dangerous to introduce animal tissue into a human being, but it would result in the patient being seriously depressed when he realized he had been duped.

The Power of Radio

However, Doctor Brinkley had long since mastered the art of getting positive publicity.

He understood the 1920s was a time when many Americans felt overwhelmed by all the new technology and new inventions; they did not know who could be trusted or believed. Brinkley positioned himself as somebody who would always tell the public the truth and who would let them know the “hidden secrets” of good health that certain un-named forces in the medical establishment did not want people to know about – a tactic still successfully used by charlatans today.

Brinkley told anyone who would ask that his surgeries were wildly successful, and some journalists actually printed enthusiastic articles about this miracle man who could help older men recover their lost potency.

Typical was an article from April 1923 claiming Doctor Brinkley was the toast of Japan, where physicians all were copying his methods. Evidently the source for this claim was found to be the good doctor himself.

By many accounts, he was a charismatic and very persuasive speaker, as well as an excellent interview. As word of his many “successes” spread, thousands of people descended on his Milford hospital in hopes of getting the secret to eternal youth. Still, being a success in Milford was not enough for John R. Brinkley. The radio craze was sweeping the country and Brinkley saw an opportunity to spread his message nationally as well as giving himself even more publicity.

The Radio Doctor

In September of 1923 Doctor Brinkley got a license to put KFKB on the air, the call letters were to stand for “Kansas’ First, Kansas’ Best.”

KFKB was on 1050 kHz with 1000 Watts – far more than most stations of that time – and used the slogan “The Sunshine Station in the Heart of the Nation.” Much of the station’s schedule of programs was like any station of the early 20s: music performed by local artists, lectures by educators (including French lessons from a nearby college), and church services on Sundays.

But KFKB had one unique feature: listeners could write in with their ailments and Doctor Brinkley would prescribe medicine for them, even though he did not know them and was only going by the descriptions they sent to him.

Brinkley dispensed medical advice several times a day and his nightly show “The Medical Quesion Box” became quite a sensation. It probably was not a coincidence that the medicines he prescribed just happened to be sold in his very own pharmacy.

All this turned into quite a lucrative endeavor for the doctor, as eager listeners sent money to get the medicines they were told would cure them.

Whom Do You Trust?

In fairness to radio audience of the 1920s, the healthy skepticism of our Internet age had yet to develop.

In 1923, a man who said he was a doctor (and claimed to have a number of degrees), had his own hospital and even operated a pharmacy sounded very credible to the average person. Plus it was more difficult to check the veracity of the claims Doctor Brinkley was making. And while dissatisfied listeners today can complain to agencies like the FCC, back then the FCC had yet to be created.

However, Brinkley had at least one influential critic. His name was Dr. Morris Fishbein, an actual doctor with a reputation for writing books and articles debunking the quacks and phonies of medicine. Thanks to their exposure on radio, some of these fakes were gaining in popularity and Dr. Fishbein was not happy about it.

Dr. Fishbein thought it was bad enough when these fakers advertised in newspapers or found new customers at county fairs.

Dr. Morris Fishbein

As the editor of the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association, he had the ear of thousands of legitimate physicians and the mainstream media took him very seriously. So, he began speaking out about what he saw as the danger from the growing number of radio charlatans, Doctor Brinkley among them.

Attack and Counter-Attack

Part of the problem was that the same newspapers which published Dr. Fishbein’s opinions often published positive articles about some of the people the doctor was trying to debunk at the same time.

A master of the art of publicity and self-promotion, Doctor Brinkley was able to persuade a number of newspapers that he was being persecuted by the cold-hearted and greedy medical establishment. Referring to himself as “the Radio Doctor,” he said that all he was trying to do was to help people in need – yet “Dr. Fishbein and others were trying to silence” him.

Brinkley told sympathetic newspaper reporters his enemies were jealous because he could cure people and they could not. When the American Medical Association’s criticism of him intensified, he played the religion card: he did a series of interviews in 1926 in which he claimed that God had told him to do these operations, “for the good of humanity.”

He claimed his station was losing money but he planned to persevere because God wanted him to; he claimed to be what today we would call a born-again Christian. He also began to state his opposition to evolution and other modern ideas that he said were satanic. And he told interviewers about all the charity work he and his wife Minnie loved to do.

He also promised to dedicate more airtime to the preaching of the gospel.

While he did add some more religious programming to KFKB, but the only gospel Brinkley preached was the gospel of consumerism, encouraging listeners to keep buying the amazing medicines he was selling. He had a very warm and conversational radio delivery, and was able to sound like the listener’s favorite uncle.

His frequent radio talks helped to turn the public’s attention away from critics like Dr. Fishbein and win new believers, as he grew even wealthier in the process. Nevertheless, Dr. Fishbein was not about to give up without a fight.

Appalled by Doctor Brinkley’s popularity, and convinced that this man was no hero, Fishbein saw Brinkley as somebody who was giving people false hope while lining his own pockets at their expense. If there was a way to get Doctor Brinkley off the air, Morris Fishbein was determined to find it.

It would not be until 1930 when Doctor Brinkley’s string of successes came to a surprising halt. And while Dr. Fishbein certainly played a role, he was not the one who caused Doctor Brinkley to have to say goodbye to both Kansas and KFKB.

Called to Account

According to Gene Fowler and Bill Crawford in the book Border Radio, Doctor Brinkley’s troubles began when he got a power increase for KFKB.

The Kansas City Star newspaper operated a radio station too (WDAF), but their request to the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) for a power boost was denied. Needless to say, executives at the Star were not amused. They launched a series of exposés on the Radio Doctor and suddenly KFKB was under scrutiny from fellow broadcasters in addition to the American Medical Association.

Never one to miss an opportunity, Dr. Fishbein did write an editorial in the AMA’s Journal, reminding everyone that he had always said the Radio Doctor was a quack. The bad publicity, which included exposés by several more newspapers, soon reached both the FRC and the Kansas State Board of Medical Examiners.

Suddenly, the fact that the Radio Doctor had thousands – maybe millions – of fans, had donated to all sorts of charities, and was generally seen as a philanthropist and good Samaritan by his listeners, no longer mattered. Questions were raised about his prescribing over the air, as well as his claims that his patent medicines could cure most diseases.

At first, Brinkley tried his famous charm, but the Medical Examiners continued to investigate. He then turned to his attorneys and filed law –suits, saying he had been libeled. Spurred on by the AMA, the Kansas Board of Medical Examiners did what it should have done years ago – it took away his license to practice medicine.

The FRC was not intimidated either. Six months after the Kansas Board of Medical Examiners made its diagnosis, the FRC voted 3-2 that Brinkley’s station was not broadcasting in the “Public Interest” – but only in his own personal interest. He appealed, but to no avail.

A Pitched Battle

Still, Brinkley was not about to give up without a fight.

He decided the best arena was politics and, in September of 1930, he launched a campaign to become the governor of Kansas. Using his well-honed public speaking skills and some populist rhetoric, he portrayed himself as a Christ-like figure, persecuted by elitists who were jealous of his success.

He understood that many people in Kansas were already suffering as a result of the Great Depression and he campaigned on a platform of lowering taxes and standing up for the average person against those who had brought Kansas such economic and moral decline. Tapping into popular anger and resentment, as well as suspicion of politicians, he pledged he would be totally accountable to the public and that he would improve the Kansas economy.

Although he was a write-in candidate, he was so popular that he nearly won the election. He got over 180,000 votes (some of the signatures he gathered were judged to be fraudulent and excluded from his vote total), an amazing testament to how much people liked him and believed what he said.

Brinkley was determined to run again for governor of Kansas, since he truly believed he had been robbed. In fact, he ran twice and each time he got fewer votes.

Heading South to the Border

While it seemed his luck had run out in Kansas, he was by no means finished with broadcasting, nor with his so-called medical career.

Doctor Brinkley sold the physical assets of KFKB for $90,000 and was ready for his next great adventure. He was also ready to reinvent himself in another part of the country – and Texas seemed as good a place as any.

In April of 1931, he announced his plans to build a high-powered radio station in Villa Acuña, Mexico, just across the border from Del Rio, TX. He promised the town fathers in Del Rio that he would bring lots of business to their town; they evidently accepted his assertion that he had to leave Kansas due to petty jealousy and the vendetta the AMA had against him.

He persuaded them that he had done nothing wrong and was ready to bring his successful medical practice to Del Rio if the community wanted him there. They did, proving yet again that there was an endless supply of gullible people.

In 1932, Doctor Brinkley, his wife and son, officially moved to Texas and he prepared to put his new station, XER, on the air. With 75,000 Watts, more than any station in the United States, XER could be heard hundreds of miles away, in cities all over the US. Doctor Brinkley was back in business.

For a while, Doctor Brinkley appeared unstoppable. His lavish mansion was a tourist attraction. He brought in as much as $30,000 a week, and he owned a yacht, a private airplane, four limousines, and the aforementioned villa. He traveled to foreign countries where he was greeted like a dignitary.

Border Blasters

Brinkley was not alone in finding a home in “Border Radio.” A number of broadcasters who had been denied licenses in the States found it easier to get on the air in Mexico, among them Norman G. Baker, owner of XENT in Nueva Laredo.

Baker had owned station KTNT (“Know the Naked Truth”) in Muscatine, Iowa, from which he pedaled as many phony medical cures as Doctor Brinkley. Baker also had no medical degree, having come from a career as a mind-reader and psychic in vaudeville. He claimed he could cure cancer and used his station to promote his “hospital.”

When he, too, ran afoul of the Federal Radio Commission, and the medical establishment in Iowa tried to shut down his medical practice in 1931, Baker simply packed up and headed for Mexico, where his station got permission to use 150,000 Watts.

Meanwhile, Brinkley was busy bringing lawsuits against journalists whom he believed had unfairly maligned him. In 1932 he sued the editor of the Amarillo (TX) News-Globe – who had accused the Radio Doctor of being a phony and a quack.

None of the expensive suits were successful, but it seemed to give Brinkley yet another opportunity to present himself as a misunderstood and unfairly reviled miracle worker. Perhaps he had used the persona of a persecuted saint for so many years that he had come to believe it. Unfortunately the courts did not have such faith.

By the late 1930s, his determination to sue anyone who criticized him would lead to his downfall. With little success, he eventually gave up on his dream of getting back at his enemies in Kansas and concentrated on running his medical business in Texas. He also continued to garner plenty of publicity, both for his station and for the money he donated to local causes in Del Rio.

A Popular Station

In fairness to the Radio Doctor, the programming on XER was more than just his medical shows.

He also gave exposure to many excellent performers, including a talented soprano named Rosa Dominguez, popular singing cowboy Roy Faulkner (who had also worked for Doctor Brinkley at KFKB), a variety of bluegrass musicians, and even a yodeler or two. He stayed on the good side of the Mexican authorities by hiring some Mexican vocalists and orchestras.

On the other hand, he broadcast programs by his “personal astrologer” (a woman who used the name Rose Dawn) and a other shows by faith healers, numerologists, and mind-readers.

But Doctor Brinkley was about to see his run of good fortune come to a halt.

More Trouble With Authorities

While XER could be heard throughout the United States, including in Kansas, some in the Mexican government were not happy about the sudden influx of Americans running “Border Blaster” stations.

The cures the Radio Doctor promised – and he had long since moved beyond relying solely on goat gland surgery to espouse new and exciting miracle drugs and even better surgeries – were causing increasing skepticism among print journalists.

Despite the expensive prizes the Radio Doctor had been offering his listeners and the large number of people who came to see him at his clinic, the Mexican government began to feel that he was doing more harm than good. They started citing Doctor Brinkley for several minor violations. Arrogantly, he ignored them, determined to boost the power, with or without government approval.

Given the strained relationship he developed with the Mexican authorities, it was not surprising that when he wanted to increase XER’s power, he ran into resistance. Ultimately the government of Mexican decided it was time to take stronger action, rather than just sending him letters or threatening to fine him.

Some sources say the American Federal Radio Commission had been encouraging the Mexican authorities to stand up to the Radio Doctor, no matter how many fans he had; other sources say it was American stations like WGN in Chicago who demanded action, since their signals were being interfered with by XER. However it came about the Mexican government finally did act decisively: by early 1934, XER was off the air.

Diversionary Approach

But getting rid of Doctor Brinkley was not going to be that easy.

The Radio Doctor told the newspapers that it was all a big misunderstanding. He claimed he was on good terms with the Mexican authorities and said he had sold XER to a local business-woman named Esther O. De Crosby.

However, a closer look showed that he was really still calling the shots. In September of 1935, XER was reborn – returning to the airwaves as XERA, 840 kHz on the dial. This time, according to most newspaper reports, the Radio Doctor was finally able to get his power boost. XERA had the equivalent of 500,000 Watts, thanks in large part to his engineer, James Weldon.

The Radio Doctor told anyone who would listen that actually XERA had over a million Watts –and thus was the most powerful station in the world.

But the good doctor’s ego was about to contribute to his final downfall.

A Rapid Fall

When his old nemesis Dr. Fishbein published yet another highly critical article about Doctor Brinkley in 1938, calling the Radio Doctor a charlatan and a fraud, Doctor Brinkley sued, asking for $250,000 and claiming the AMA’s persecution of him had hurt his business.

The case made its way slowly through the courts but, although Brinkley was able to bring in various “witnesses” who attested to the man’s saintly qualities, the evidence showed that Doctor Brinkley was not all that he claimed to be. The court sided with Dr. Fishbein. That seemed to open the proverbial floodgates, as suddenly disgruntled patients appeared and spoke out about how disappointed they were with Doctor Brinkley’s work. Some even initiated lawsuits of their own.

With even more scrutiny upon his life and his business, the IRS stepped in and told him he owed back taxes – lots of them. With former patients suing and the IRS demanding payment, suddenly the untouchable Doctor Brinkley was in deep trouble.

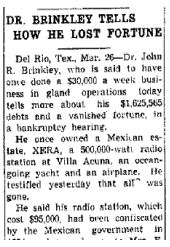

A March 1941 newsclipping

By 1942, he had declared bankruptcy and many of his assets were seized to pay his outstanding bills. The hospital he ran in Del Rio and another he had opened in Little Rock AR in 1938 were also closed down.

XERA was no more, closed by the Mexican government. Brinkley and his wife were about to be prosecuted for mail fraud. For all of his promises about giving patients eternal youth and virility, Doctor Brinkley himself suffered a heart attack and died in late May 1942.

He was only fifty-seven.

Legacy

It would be nice to say that the world learned something from the rise and fall of Doctor Brinkley, but as Barnum’s apocryphal quote points out, there is no shortage of suckers, even in our modern era.

We have Internet scams, pyramid schemes, plenty of late-night TV infomercials, and, of course, commercials regularly heard on the radio, promising to cure baldness, improve memory, add years of life, or give one much more energy.

Even now, the legacy of Doctor John R. Brinkley lives on.

– – –

If you would like to learn more about J.R. Brinkley, you might be interested in the book The Bizarre Careers of John R. Brinkley from the University Press of Kentucky or Border Blasters from the University of Texas Press.

– – –

Media Historian Donna L. Halper writes on a variety of radio historical topics when she is not consulting radio stations, writing books, or teaching at Lesley University, Cambridge MA.

You can contact her at: dlh@donnahalper.com