Joe Pyne – Talk Radio Pioneer

[June 2017] Talk Radio has been a major format on radio for over 50 years. From Little Joe Little to KDKA’s Party Line to Rush Limbaugh, and so many more, the one that really changed American talk radio was Joe Pyne’s talk shows.

The modern talk show format is known for heated debate and angry confrontation, but the father of that style of talk came from the 1960s, a time when talk radio was usually much more courteous

Joe Pyne did not believe in being courteous. He said on many occasions that he was not a nice guy, and he did not want to be a nice guy.

In an era when talk shows were just coming to the forefront, Pyne’s nasty on-air persona took him to the top of the ratings. He was one of broadcasting’s truly unique figures, detested and criticized by some, admired and emulated by others. But as polarizing as he was, it cannot be denied that he changed how the talk show was done.

A Marine From PA

He did not start out with dreams of being a talk show host.

Joe Pyne was born in Chester PA, on December 22, 1924. His father Edward was a bricklayer, and his mother Catherine a homemaker. Joe’s family moved to Atlantic City when he was five. His childhood was marred by losing his younger brother, who was killed in an auto accident when Joe was eleven.

The Pyne family returned to Chester in time for Joe to attend Chester High School, and after graduating in 1942, he joined the Marines. In intense combat in the South Pacific, he earned three battle stars. In 1943, he also received a purple heart as a result of a serious wound to his knee during a Japanese bombing of his Marine base.

Years later, in 1955, he would find that he had a rare form of cancer in that leg, requiring an amputation. From then on, he wore a wooden leg, which went along with the image he developed of being a tough ex-Marine.

Drama School to Radio

When he came out of the service, he first decided to attend a drama school where he could correct a speech impediment and become a better speaker.

Not knowing what he really wanted to do with his life, he was driving a taxi in Chester, but as he became more confident about his speech, he thought about broadcasting as a career.

It was the late 40s were a time when nearly every city had a local radio station or two, and they always needed live announcers. So, he went to work for the new station in Lumberton NC, WTSB in 1946 – the pay was only $25 a week, and with few signs he would ever advance, within a year, he had returned to Chester.

Pyne was soon hired by the newest station in the area, WPWA in Brookhaven. However, in what would be a pattern in his life, he got into a dispute with the owner and ended up getting fired after working there only six weeks. His next job was at WILM in Wilmington DE, the first of three times he would work at that station, but here too, his stay was brief, and then it was on to another new station, WVCH in Chester in March 1948.

A typical radio gypsy, Pyne next went to Kenosha WI, where he was hired at another new station, WLIP, which had only been on the air since May 1947. Once again, Pyne got into a dispute with the station owner, William (Bill) Lipman, and got himself fired; he had lasted about six months.

A Change in Format

The last experience was not a total loss, however. It was in Kenosha, according to some sources, that Pyne first began to experiment with talk.

Instead of just playing records, he started making comments about politics and current events, which was not something he had been hired to do. WLIP was a community-oriented station, and in the post-war era, commentators were still members of the news department; announcers and disc jockeys played music and read commercials. It is not surprising that Bill Lipman wanted him to stick to playing the hits and interviewing local businesspeople.

It’s Your Nickel

By this time, Pyne was convinced that being a small town disc jockey was not for him.

He did like being on the air, but he wanted to do something far more interesting than attending county fairs or going to the openings of new stores, which small town announcers were expected to do. At his next job in Atlantic City NJ at WFPG, he continued to work on his new idea: never shy about expressing an opinion, he had decided to turn that trait into a radio show where he could express his opinion about the issues and interact with the listeners.

Pyne had seen night-club comics using sarcasm to comment on current events; the more he thought about it, the more he decided it could work for a talk show. So, he returned to WILM in 1951, where he created a new show that he called “It’s Your Nickel” – the name referred to the fact that in the early 1950s, it cost five cents to call from a pay phone.

Building a Reputation

For the next six and a half years, Joe Pyne would develop a reputation as an abrasive, controversial, and confrontational air personality.

For the next six and a half years, Joe Pyne would develop a reputation as an abrasive, controversial, and confrontational air personality.

That he was able to do so is actually quite surprising. While talk radio was quite new at this point, the FCC was concerned that stations would misuse their power by preventing the discussion of opposing viewpoints.

Therefore, the FCC mandated a rule called the “Fairness Doctrine” in 1949, stating that since radio station owners were public trustees, they had a duty to present the contrasting sides of the issues, and to allow responsible spokespeople to defend themselves if they felt their viewpoint had been unjustly attacked.

And yet, even in a conservative time, when radio stations were taking very few chances, Joe Pyne took the biggest chance of all in creating a show that was neither polite nor unbiased.

Today, the rude and angry talk host is all too common. In the early 50s, Joe was undoubtedly the first.

It’s Your Nickel, But My Show

On “It’s Your Nickel,” the show began benignly enough.

In his nightly introduction, he said, “The mike is open. My name’s Joe Pyne. I guess you know yours. This program is dedicated to the free exchange of ideas and to differences of opinion. I don’t propose to have all the answers, but I do promise to talk about the things that interest you.”

However, from there the show quickly became a shout-fest, with Pyne definitely in control. No topic was sacred, from sex, to religion, to politics. But when he felt a listener had gone on for too long or was making no sense, he would make a rude remark like “You’re sick!” and hang up on the person. Enduring Pyne’s abusive rhetoric was the challenge for the audience, many of whom tried to debate him before he hung up on them.

His views tended to be quite conservative most of the time, and Pyne seemed to dare his listeners to disagree with him.

His style of arguing included using very derogatory terms. Known for being adept with words, his arsenal of insults and put-downs became the stuff of legends. Among his best known were “If your brains were dynamite, you couldn’t blow your nose.” There was also “Go gargle with razor blades,” and “Take your teeth out, put ’em in backwards and bite your throat.”

Guests Got it, Too

Pyne could be as abrasive with guests as he was with callers, and he seemed to enjoy making controversial statements to the media.

He told reporters that radio was geared to the mentality of a thirteen year old, and that the average American was both apathetic and easily persuaded. He also insisted that he was making a positive contribution because he was making people think. This was a stance he would continue to maintain, telling the Los Angeles Times in an opinion piece in 1965 that while some people called him “a rabble-rouser and a hate-monger,” all he was trying to do was encourage some “stimulating dialogue.”

The critics were not so sure. While they found him quotable, they did not perceive his often angry style as stimulating; rather, it often made them uncomfortable. And the longer he remained on the air, the more the critics wondered how he managed to keep his job.

Yet, it was not just the critics who were ill at ease about what Pyne was doing on the air. His outspokenness made him enemies in Wilmington, where he didn’t just comment about national issues: he criticized Delaware’s attorney general, Wilmington’s mayor, and several other local political figures. Perhaps that was why the audience kept listening: you never knew what you would hear when Joe Pyne was on the air.

Moving On Up

Then, in May 1957, Pyne decided he had been on the air at WILM long enough.

He had made a name for himself, earned a salary in excess of $42,000 a year (excellent money in the 1950s), inspired plenty of controversy, and even fended off a number of threats of violence from disgruntled listeners and guests.

But now it was time for a new challenge, and he headed for the West coast.

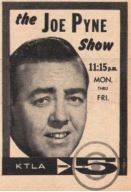

At first, he could not find a radio job, but finally landed one at a station in Riverside CA, 60 miles from Los Angeles. That led to an opportunity on a Los Angeles television station, KTLA.

Now, he was on the West coast, in one of America’s largest cities, doing a TV talk show.

Now, he was on the West coast, in one of America’s largest cities, doing a TV talk show.

Pyne would later claim his new show had been a big success.

Yet within a year, he was back in the Chester-Wilmington area again, doing a brief stint on a Philadelphia TV station (WVUE-TV), and then going back to WILM.

He told reporters that he was just biding his time, that he had plans. And those he certainly did.

Polishing the Format

He moved back out to Los Angeles, and by the early 1960s, he was doing his usual angry and abrasive talk show at KABC.

Once again, he polarized the audience, with some listeners and guests complaining he was too caustic and others saying his candor was refreshing. But as in Wilmington, he had people talking about him and his show.

From KABC, he went over to KLAC in 1965, doing the 9 MM to Midnight shift. Never one to avoid controversial guests, he put Nazis and members of the Ku Klux Klan on the air, earning the displeasure of the American Jewish Committee and a warning from the FCC. He also had guests who believed in eugenics, guests who were racists, guests with strange theories about past lives or UFOs – and the arguments continued.

He was back to making a big salary – at that time about $200,000 a year by some estimates – and getting plenty of attention from the critics, as well as lots of listeners.

Going National

And then, along came his biggest opportunity: syndication.

The NBC Radio Network began syndicating his show nationally in March 1966; it was soon carried by over 200 stations. Billed as “fist in the mouth” radio, Pyne did not disappoint. It was the same rage, the same controversial guests, the same insults – and the same results. While the critics were disgusted, his fame spread and he continued to attract large audiences.

One thing that was different was the time slot: where in the past, Pyne had mainly done his show at night, this time, he was on during the mid-morning.

In an era when women were still homemakers, having an outrageous talk show on the air at that hour was actually a bold move.

To the consternation of those who disliked him, it worked.

You Won’t Turn Him Off!

One station that was about to become an affiliate in 1967 placed a large advertisement in the local newspaper, explaining what the Joe Pyne show was all about, listing some of its famous (and infamous) guests.

The ad concluded with “You may agree or disagree with Joe Pyne. You may scream in rage at some of his remarks. BUT YOU WON’T TURN HIM OFF!” It was true. Even in ‘housewife time,’ he continued to win new fans.

And Joe Pyne was not finished with surprises. He was negotiating for the opportunity to syndicate the television show he had been doing on KTTV (Channel 11) in Los Angeles. In LA, Pyne’s legend had grown after he had argued with black militants on his show – when the debate had become too heated, he opened a desk drawer to show that he kept a revolver hidden, just in case.

The TV show did get a syndicator, and soon he was not only heard nationally on radio, but seen nationally as well. On the national TV show, he not only had more controversial guests (including followers of cult-leader and convicted murderer Charles Manson), but also showcased an array of eccentrics, as well as people with unpopular views (such as homosexuals, who back then were regarded as mentally ill).

Not a Gracious Host

Pyne regularly made fun of these guests and ridiculed the way they lived or how they looked.

Now and then, he invited a celebrity guest, but he seemed to prefer only those guests who were controversial in some way. In 1965, Helen Gurley Brown, publisher of Cosmopolitan magazine was on his TV show. She was a woman known for her open-minded views on sex, and she did not disappoint, discussing on air why women should exercise by dancing naked.

Most of Pyne’s guests, even those who were well-known, seemed to be there so he could argue with them and fire up the viewers. He even had a feature where members of the studio audience could come up and step into what he called the “Beef Box,” and get their chance to complain about something. They also got their chance to have Pyne insult and disagree with them.

But that did not stop them from coming up and complaining.

The Frank Zappa Non-Story

Because Pyne was so rude and confrontational with guests, there are stories about the rare times when somebody got the better of him.

For example, there is a much-quoted story about how he lost a verbal duel with rock star Frank Zappa. Pyne, a supporter of the Viet Nam war, had an intense dislike for “hippies”, especially men with long hair. He immediately insulted Zappa by saying, “So I guess your long hair makes you a woman.” Zappa allegedly responded, “So I guess your wooden leg makes you a table.”

The problem with this story is that while it sounds plausible, and it has been repeated on the Internet and in magazines, nobody who was around at that time recalls it happening, nor is there any evidence from that era that Zappa was on the Joe Pyne Show. With no concrete proof, most media historians have concluded the story is an urban legend.

Paul Krasner: Same Non-Story?

Similarly, there is another, much-quoted confrontation that may or may not have occurred, involving author and satirist Paul Krassner, who actually was a guest on Pyne’s TV show.

The account says Pyne started to make insulting remarks about Krassner’s acne scars. Krassner quickly struck back, asking Pyne if his wooden leg caused any difficulty in having sex with his wife. As the story goes (and Krassner has told it numerous times), Pyne was rendered speechless, so stunned by Krasner’s audacity that he went to his studio audience for moral support.

However, Krassner had brought folksinger Phil Ochs along with him, and Ochs immediately spoke up on Krassner’s behalf, saying that Krassner had just given an example of American journalism at its finest. Another great story, but once again, while Pyne’s detractors want to believe it must be true, the video that exists from that show does not have any of this particular incident. Krassner, nevertheless, is adament that it did occur and he has said it must have been edited out.

Never Give In

Despite being very willing to have astrologers and psychics and faith healers of all kinds on his show, Pyne tended to be a skeptic. Inevitably, this led to heated arguments – that was his format, after all.

Over the years, no matter how heated the exchanges were between Pyne and his guests, he never backed down. In fact, he even dared disgruntled guests to sue him. One actually did so: in 1967, a chiropractor named J. Bernard Jensen said Pyne had slandered him and done damage to his reputation. But the judge threw the case out.

An interesting aspect of Pyne’s career occurred in July of 1966, when he briefly became a game show host. He was the master of ceremonies for “Showdown,” which was a summer replacement that only lasted three months. There is no evidence that anyone argued, and no chairs were thrown, but for people accustomed to Pyne as the angry talk host, seeing him MC a game show must have been somewhat surreal.

Running Out of Time

But while his career continued to be a success, something in his personal life was about to catch up with him.

Pyne had been a chain smoker for years, even smoking on the air and being very vocal about his right to continue smoking. He was diagnosed with lung cancer, and after doing his show from a studio in his home for a while, he had to stop the broadcasts in November 1969 to undergo treatment.

By the time he finally did stop smoking, it was too late.

Pyne’s Legacy

The “King of the Provocateurs” died in Los Angeles, on March 23rd, 1970. He was only 45.

Remembering his career, someone who worked with him said that throughout his career, Pyne had “wanted to be powerful and feared. He never lost control in any situation.” The persona he created, of the intimidating talk show host who shouts down the guests and insults the callers, can be found in a number of today’s talk radio hosts. It may not be right for everyone, but contemporary hosts like Michael Savage have become quite successful doing perpetual outrage.

And yet, even forty years later, some media historians insist that nobody has ever done it quite as well as the original angry talker, the late Joe Pyne.

– – –

Donna L. Halper, PhD is an associate professor of Communication and Media Studies at Lesley University, Cambridge MA. She is the author of six books and many articles, a radio consultant and a former broadcaster. Her website is: www.donnahalper.com